In my Bible study with my church recently, we talked about Acts 4-5, which include the account of Ananias and Sapphira being immediately struck down for their deception in selling land and donating the proceeds. This passage raises some interesting questions, and I am curious about its implications for Christian ethics, if any. In this article, I will explore what these verses might imply about the relative badness of lying and killing, the value of human beings, and the badness of sins against God.

In this article, I defend the view that human beings are infinite valuable, some sins are worse than others, not all sins against God are infinitely bad, a particularly egregious sin against God may warrant eternal punishment, and that God’s judgment against Ananias and Sapphira is warranted by features specific to the 1st century church. Join me for the ride!

Note: This is a long post, so feel free to skip around to the sections of particular interest using the linked section headers below. Additionally, this post is available as a PDF or Word document.

- Some Introductory Questions

- Justice and Punishment

- The Badness of Killing and the Value of Humans

- Are All Sins Equally Bad? The Disvalue of Lying vs Killing

- Contextual Specificities (Why Ananias and Sapphira are Special)

- Conclusion

- Endnotes

Some Introductory Questions

A question that is often asked of the Acts 5 account of Ananias and Sapphira (A&S) is: why is lying deserving of death? People wonder what the exact sin was that Ananias and Sapphira committed when they told Peter that the money gave was the full proceeds from selling the field when, in actuality, it was less than the full proceeds. Ananias and Sapphira were killed immediately upon their proclamation (or implication) that they had donated more than they, in fact, did donate. Were they killed for lying? Acts 5:4 says that “You have not lied just to human beings but to God.” So, it appears as though lying was the sin for which they were killed.

Was there something special about the nature of their lie that made it special compared to everyday instances of direct lying in my own life? I think the answer is “clearly not.” We are not told any details that would differentiate this case of lying or deception from any other case of lying, even though this case was considered lying to God (and Acts 5:3 specifically says it was lying to the Holy Spirit). If Acts 5:3 exhibits parallelism of repetition, then the lie to the Holy Spirit just was keeping the money back, not something especially externally differentiable from typical lies. I think one implication of this passage might be that, since their lie was obviously relevantly similar to everyday direct lies, that every lie against humans is also a lie against God. This generalizes the concept of sins against God.

However, this doesn’t help us at all with the original question, which is that why is a lie, even a lie against God, deserving of death? In order to answer this question, we need to get into a few things, including 1) the nature of justice and punishment, 2) the badness of killing and the value of humans, and 3) the disvalue of lying vs killing, particularly against an infinite being 4) contextual specificities.

Ultimately, I think that the judgment against Ananias and Sapphira will rely on certain facts specific to their context, but I think for a fuller picture, we will need to investigate broader facts of Christian ethics, such as the infinite value of humans, inequality of sins, infinite sins, and the first century church context.

Justice and Punishment

I won’t talk about this long, but we need to briefly talk about divine justice and punishment. Although the passage does not explicitly say that God struck A&S dead, saying instead that they “fell down and died” at the moment Peter pronounces their wrongdoing, it seems apparent that the passage portrays the deaths of Ananias and Sapphira as a kind of divine punishment, an administration of justice. Justice requires the punishment of wrongdoing, so justice demands that the sin of Ananias and Sapphira be punished.

The requirement of punishment does not demand immediate punishment, but it does require proportional punishment. The punishment given should be deserved by the wrongdoing. So, divine punishment will be proportional to the magnitude of the wrong or evil act. Sometimes, people say that all sin is equally bad (because it is all sin against an infinite God). I will come back to this idea. This idea is counterintuitive, so it would be a strike against a Christian ethic to have this entailment that all sins are equally bad.

So, the punishment for lying must be proportional to the wrong of lying. I think it (reasonably) strikes many of us as disproportionate to kill someone for lying, including the magnitude of the lie of Ananias and Sapphira. I will come back to this. The point is that, somehow, we need to square how an apparent punishment of death is proportionate to the wrongdoing of lying. To answer this question, we need to know how bad killing is.

The Badness of Killing and the Value of Humans

Death is bad. I won’t get into a debate on the badness of death itself, but what is relevant here is not mere badness of death, but the badness of killing specifically. If God struck down Ananias and Sapphira, then God intentionally killed Ananias and Sapphira. Perhaps, as I saw some website propose, God merely withdrew his support and protection from them, and since no one can survive without that, they immediately died. Therefore, on this view, God merely let Ananias and Sapphira die, not killed them. This is a great example of why this distinction between killing and letting die is, at times, so ridiculous to not be taken seriously (at least in terms of value differential). In any case, I think killing in a case where you have the legitimate option to save someone from dying (i.e., prevent letting them die) is not significantly worse than “letting die”. Plus, to best respond to the objection, we can respond to the hardest case to deal with, which is killing, rather than any attempt to weaken the act of God to be less bad.

Okay, so God killed two people as a punishment for lying. How bad is killing? I would think that letting die or killing is at least as bad as the value of the person in question. This is true even if, on a technicality, humans do not cease to exist upon death.[1] Human lives have value simply in virtue of being human lives. To deny this results in extremely problematic implications for the value of those with severe cognitive impairments.[2] So, taking human life seems to be as bad as the value of a human life.

How valuable is a human life? Plausibly, a human being is infinitely valuable. There is a long tradition of Christians affirming the infinite value of humans. Admittedly, I have rarely seen this explicitly discussed, especially by analytic philosophers, and I have seen almost no explorations of its implications for Christian ethics. If anybody can point me to substantive discussions of this in the Christian tradition (or anywhere), please do!

The Case for the Infinite Value of Humans

By far the most extensive discussion of the infinite value of humans that I have seen is in the paper “How Valuable Could a Person Be?” by Andrew Bailey and Josh Rasmussen.[3] I have found this to be a convincing argument that people are infinitely valuable. The argument relies on two basic and widely accepted ideas, which are the equal and extremely high value of people, and it suggests that the infinite value of people would explain both the equal and extreme value of people. The argument can be structured as below (or as a Bayesian argument[4]):

- People are equally valuable.

- People are extremely valuable.

- The best explanation of (1) and (2) is that people are infinitely valuable.

I take it as a given that all humans are equal. Every person is equally valuable. No human is superior to any other in their moral worth or dignity. The equal value of humans is true regarding either their intrinsic (non-instrumental) value or their total value (including intrinsic + instrumental), as the argument works either way. I think it is more plausible on the “intrinsic” value version (usually called “final” value in the ethics literature), which focuses on value for its own sake or as an end in itself. In moral evaluation, every human is intrinsically worthy of the same consideration, even if their instrumental value may differ and will affect the overall moral evaluation. Therefore, I take the first premise to be on extremely solid ground. To deny the equal (intrinsic) value of humans is a pretty insane result with catastrophic consequences.

I also take it as a given that people are extremely valuable. Human life is precious, and it should not be taken lightly or whimsically. It is a very good thing that you exist, and you are more important than every star or donut or animal or sunset that has ever been. Something of immense value has been lost when someone passes away. Some might say something priceless is lost. So, people are extremely valuable.

The strange thing is that this combination of extreme and equal value produces a puzzle. Consider the following analogy (adapted from Bailey and Rasmussen): You go to an art museum of all the best artwork in all the world of all different kinds, styles, and methods. There are watercolor, acrylic, and oil-based paintings. There is realist, surrealist, abstract, Dada, expressionist, and (my favorite) pointillist artwork. There is art from the 1st century and every other century until modern times. There are pieces from van Gogh, da Vinci, Picasso, Rembrant, Dali, and many more. Clearly, there is a huge variety of artwork, and each of them with very different properties or properties expressed in different ways and to different degrees, each expressing aesthetic value.

You approach the museum curator and ask, “How much are each of these paintings and beautiful variety of artworks worth? This is an incredible and varied collection.” The curator responds, “Each and every single piece in the museum is worth exactly $37,635,127,099.74.” You would be incredulous! “I’m sorry, what?! Every single piece, from the most realist to the most abstract, from the 1st to 21st century, from da Vinci to van Gogh, is worth exactly and precisely thirty-seven billion, six hundred thirty-five million, one hundred and twenty seven thousand, ninety-nine dollars and seventy four cents?!”[5] The artistic experts came in and looked at the wide variety of art and its beauty exemplified in very different ways displayed throughout the museum and, assuming they were attempting to price exactly according to their aesthetic value, thought they had equal and extreme aesthetic value.

This would be bizarre! An incredible, unbelievable coincidence. It is so unbelievable, I would suggest, that it is literally unbelievable. You should not believe these artworks have identical aesthetic value, particularly when it appears to be so arbitrarily applied to end up with equal worth, down to the level of cents. At the least, this equality would demand a very good explanation, one that is not forthcoming.

Hopefully, the analogy is obvious. Humans come in a wide variety of shapes, sizes, colors, and a wide variety of properties exemplified in different ways to different degrees. The human race is relevantly similar to a museum of the finest artwork, not necessarily with respect to aesthetic value (though I think the human race does include great aesthetic value, and a subset of them may be museum worthy), but with moral value.

We all differ in numerous ways, many of which people take to be morally significant. When we ask what makes humans uniquely valuable, especially in comparison to various other animals, the answer usually is something in the ballpark of: cognitive capabilities, consciousness, intelligence, self-awareness, rationality. Alternatively, one can give explicitly morally significant properties, such as moral deliberation and having moral intuitions or things like that. The trouble is that it seems obvious that each of these properties are degreed properties. One can exemplify self-awareness or rationality to different degrees, and some humans are better at moral deliberation or performing various cognitive tasks compared to other humans. This observation is true even restricting to those without significant cognitive impairment/disability, as Eistein is obviously much more cognitively capable than me, and some people are more reflective and self-aware than others.

Yet, humans are still equally valuable, in spite of their many differences in these properties. There are two conclusions one can take away from this. The first, which is irrelevant to my argument here, is that all human beings, independent of their cognitive status or location in time, space, or life cycle, have the same (extreme) value in virtue of being a human being.[6] The second takeaway is that humans are infinitely valuable.

The infinite value of humans guarantees the extreme value of humans (since infinity is an extremely high value), and it strongly suggests or at least can easily make sense of the equal value of humans. While I later discuss ways to get unequal value even assuming infinite value[7] there are easy and natural ways to get equal value on infinite value, especially given that equal value is a desideratum of our current reasoning. In this way, we can see that using ordinal numbers to represent various value-enhancing properties (see “Infinite Sin without Equal Sin” for discussion of infinite ordinal and cardinal numbers) would not be adequate, as the different degrees of properties in humans would lead to different values, conflicting with premise 1. So, we must use cardinal numbers (or we could all have the smallest ordinal infinite value ω). Therefore, the lowest infinite cardinal number ℵ0 makes sense for the value of humans, which would imply all humans have equal value. The next largest infinite number that we know of[8] is a quantum leap higher that could not be obtained by the finite differences in human properties, so we are justified in thinking humans would not be different levels of infinite value.

So, the infinite value of humans (ℵ0) makes perfect sense of the extreme and equal value of humans. The value of humans no longer amounts to the bizarre claim that each human is worth some arbitrarily high finite number in the trillions, or beyond that, which coincidentally is identical to everyone else’s value down to the decimal places. Human life is, in a real sense, priceless. It is limitless. The infinite value of humans answers the demand for explanation of the extreme and equal value of humans.

Figure 1: Definitive proof of the infinite value of human beings. I mean, you see the infinity symbol on the chest, right?

Richard Swinburne (and Josh Rasmussen) have given some arguments that one should prefer infinite or unlimited value over arbitrarily high finite values, where possible. For example, in the history of science, it was assumed that light traveled at infinite velocity before it was experimentally measured to be a finite velocity. Swinburne defends the view that limitless quantities are simpler and thus preferable to finite or limited quantities, all else equal.[9]

In summary, I think there is a strong case for the infinite value of humans, and I think it well explains the equal and extreme value of human beings.

The Case for the Finite Value of Humans

On the other hand, we can build a case for the finite value of humans. Probably the best case for the finite value of humans is just that the infinite value of humans appears to have some absurd implications. These implications are supposed to be sufficiently morally unacceptable to warrant the rejection of infinite value of humans.

For example, Matthew Adelstein argues some of these purported counterexamples, but his arguments have some problems. His first four counterexamples, in order, appear to 1) assume we cannot make infinite comparisons (i.e., comparisons among worlds that contain infinite value, see Infinite Sin without Equal Sin for more discussion), so we cannot conclude that an infinitely valuable human + human pleasure is better than infinitely valuable human + human suffering, 2) ignore the instrumental value of humans[10] or the difference the value of the human person (a person) and the value of the human life[11] (an event), 3) neglect the difference between the marginal vs intrinsic value of humans (see picture below), which doesn’t imply every second of a human life is of infinite value even if a human itself is, and 4) also neglects infinite comparisons (which he does this again later when saying that, on the infinite value view, saving two humans is no better than saving one human).

Figure 2: Rasmussen and Bailey distinguish the value of a human being from the marginal value of human life from the lifetime of events of a human being, and they only think the first of these is plausible.

Matthew’s next argument is that if humans are infinitely valuable, then shortening a human life by 1 second is infinitely disvaluable. If so, then shortening a human life by 1 second is worse than thousands of lethal headaches or a quadrillion animals being tortured. Therefore, humans don’t have infinite value. However, we already saw that we do not have good reason to think that the infinite value of a human being implies the infinite value of every second of a human being’s life, and the authors (and myself) already find this implausible. Matthew gives no reason to think this link is plausible. So, I am happy to conclude with Matthew that shortening a human life by 1 second is not infinitely disvaluable, but I just don’t know what that has to do with the infinite value of a human being.

Perhaps the best response to this is to argue that killing is infinitely bad and that killing is relevantly similar to shortening a human life by 1 second. The thought would be that there is an arbitrary difference between shortening a human life by 1 second and shortening a human life by force by, say, 50 years. I don’t think these are relevantly similar, but it kind of depends on if we think that killing someone is causing them to cease to exist. If killing them does not actually remove this person from the whole of reality, then it would not seem to be infinitely bad. If the whole of reality includes the past, however, it would be impossible to remove this person from the whole of reality. In fact, on eternalism, the person exists tenselessly, including past temporal stages of that person. I think that is not a morally interesting fact, but it is a fun spooky true sentence nonetheless.

The implication of the previous paragraph is just that there are some things that do challenge the idea that killing people is infinitely bad, even if humans are infinitely valuable. I think after writing this post (since I happened to write this section 2nd to last), I am definitely less confident that killing someone is infinitely bad. Yet, finite disvalue for murder I don’t think is a challenge at all to the infinite value of humans, as killing with an afterlife is merely transporting them to another dimension (or, given my version of soul sleep, only temporarily causing them to cease to exist), and killing on eternalism would merely be causing their temporal stages to not extend further into the future, not removing their existence. Since the person would not be removed from the totality of reality, then it is not obvious there is infinite value removed from reality compared to if the person were not killed.[12]

Killing only deprives a person of a subset of its full life, not of its life in its entirety. So, I think it is plausible that killing is only finitely bad to kill an infinitely valuable being. Probably the most popular view, and a reasonable one, is that the badness of killing amounts to the value of the deprivation of the value of the wellbeing that one would have had if you had not killed them. So, the badness of killing is proportional to the number of life-years you removed. I don’t think I have made up my mind on this yet.

The remaining concerning objection that Matthew raises is that it would seem to produce a paradox: if humans are infinitely valuable, then creating a human creates something of infinite value, and so everybody should have as many babies as possible (or at least we should maximize the number of humans), even if it is at significant finite cost. He says that the infinite value view implies that “torturing 1000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000 animals in order to produce one extra human would be good overall, producing infinite value at a cost of merely finite value.”

This is a really interesting and powerful objection. A similar objection is raised in a paper by Andrew Lee arguing that life has no intrinsic value, but the value of a human life is only in the goods it contains.[13] Lee raises the issue of cases where a life with intrinsic value (which would be especially true if it is infinite) would entail that even a short life containing nothing but suffering is worth living, but surely this is absurd.

I think Lee’s variation of the objection is easier to respond to.[14] It is usually agreed (with Lee) that if I know that I have some genetic defect, along with my wife, that would guarantee that any child of mine would live for a short time and experience virtually nothing but pain, I have a moral obligation to not have that child. It would be wrong to create a person whose life would be short, miserable, and consist almost exclusively of suffering (and I don’t mean something like Down syndrome). But it might seem that if I created something of infinite value, then infinite value minus the finite disvalue of suffering is still infinitely good overall (especially if this child would go to heaven and experience another round of infinite good[15]).

What this does not consider is that this child’s death is within the foreseeable consequences that follows directly from your action of having a child with a known genetic defect. Therefore, while creating this child would create infinite value, then the act of knowingly letting them die (because you knew about this defect) would be an act of infinite disvalue. These two infinite values would cancel each other out, and the only remaining value is the great disvalue of suffering, which is clearly worse than not having the child.

The response to this will likely be that anytime you create a human being, you know that they will eventually die, and so if my response works, then any act of creating a human being would not be intrinsically valuable, as it would always be offset by the disvalue of letting die, and so we are back to the view that the value of a human life is just the goods it contains. However, there seems to be an obvious difference between the “letting die” that is creating a human with a known genetic defect that follows directly from your act of creating the child in the first place, and the version of “letting die” where, for all you know, your child will end up dying of old age of natural causes, of their own negligence or bad health choices, or taken against their own will; in none of these cases do the parents have any responsibility for the death of their child, even though had they not produced the child, the child would not have eventually died. It’s just obvious these situations are wildly different.

Secondly, even if this argument fails, I’m fine with the implication that creating a human being is net neutral intrinsic value, which is still different than the assessment of the intrinsic value of humans. Creating a human being might be net neutral and the intrinsic value of humans be infinite, and the act of letting die or killing be infinitely bad.

I think this second approach might be the best response to Matthew’s objection about torturing animals to create more humans. If creating humans is net neutral intrinsically, then obviously it would be unacceptable to torture animals to create more humans. The other thing to consider for more realistic scenarios that don’t stretch the imagination to include the choice to torture a bajillion animals to produce more humans are the opportunity costs of creating more humans vs other more valuable endeavors that may also be infinitely valuable, such as ensuring more people go to heaven (which is a worthy consideration due to the risk analysis even if you don’t think there is such thing as an eternal hell but consider it to have a nonzero probability).[16]

Therefore, I think there is plenty of room to affirm the infinite value of humans even if other things, such as creating a human, killing a human, letting a human die, or hurting a human are all only finitely valuable or disvaluable. My credence in the infinite disvalue of killing has been tampered in writing this post, but I think it remains my default for the time being. It does seem to problematic reduce all of ethics down to questions of minimizing human death (or getting people on the path to heaven), which is counterintuitive, but I think can be salvaged by appealing to synergy between minimizing human death and broader moral considerations. At the end of the day, I recognize it will require biting some bullets to say killing is infinitely bad, but thankfully the infinite value of humans remains perfectly intact without this assumption about killing.

Summary

While there are good objections to the infinite value of humans that I do not know how to fully deal with, the finite disvalue of human killing has some limited intuitive appeal, and I certainly have not systematically worked through how to deal with infinite value in a moral theory, it remains extremely plausible to me that killing a human is infinitely disvaluable,[17] and I am hopeful the objections can be dealt with, even as there has not been sufficient attention given to this question. Plus, it is stronger to respond to the hardest case, so I will move forward assuming that killing is infinitely bad.

Are All Sins Equally Bad? The Disvalue of Lying vs Killing

The conclusion of the previous section is that God carried out an action that, in isolation, has infinite disvalue. Now, I am already going to grant that, assuming this punishment is warranted (and thus must be proportionate), this punishment (though not necessarily applied immediately) is the best thing for God to do, aka results in the most overall good, given the wrongdoing happened. We can easily model the retributive justice here as a composite[18] of 1) lying (wrongdoing), 2) killing (punishment), 3) the relevant relationship between (1) and (2) such that the punishment was deserved, appropriately given, and proportionate. In this way, two bads make a good (in virtue of (3)), as giving warranted punishment to a wrongdoer is morally better than letting a wrongdoing go unpunished, on the retributive view. I won’t defend but will merely assume the retributive view here.

Therefore, if killing as a punishment is proportionate to the wrongdoing of lying, then it is appropriate for God to kill Ananias and Sapphira. But surely this seems wrong?

One thing I have heard Christians say, whether in connection to this passage or in general, is that all sin is equally bad, especially insofar as all sin is against an infinite God. This principle, that the badness of a wrongdoing is related to or proportional to worth/value/status of the one who is wronged, is termed the “status principle”. One area of theology in which this claim comes out explicitly is in discussions of the justification of an eternal hell. If all sin is infinitely bad, then all sin is equally bad, and all and every individual sin is individually deserving of eternal hell. I will discuss the status principle and potential implications for our investigation.

The Status Principle, Equal Value, and Infinite Value

We can construct a straightforward argument for the view that all sin (i.e., moral wrongdoing) is infinitely evil based on the fact it is against an infinite God.[19]

- All sin is against God.

- God is infinitely worthy of regard.

- The gravity of an offense against a being is principally determined by the being’s worth or dignity. (Status Principle)

- There is infinite demerit in all sin against God. (from 2 and 3)

- Therefore, all sin is infinitely heinous.

I hope that premise two, that God is infinitely worthy of regard or infinite moral status/worth can be reasonably accepted by all. Premise 1, that all sin is against God, is more controversial, and Jonathan Kvanvig dedicates 7 pages of his book on hell to exploring this question.[20] I will leave this question for another time, as I think we can grant in this context that the sin in view with questionable disvalue, lying, was explicitly identified as a sin against God in Acts 5:4.

It may be tempting at this juncture to, if one already grants the status principle (and thus the entirety of the argument), conclude that all sin would be equally evil, since it is all infinitely evil. This temptation, however, must be resisted, as one can have 1) different infinite sins that are unequal to each other, and 2) finite sins against infinite beings, which undermines premise 4 above.

Infinite Sin without Equal Sin

As it turns out, one can have varying levels of infinitely bad sin, so even if all or a range of sins were infinitely bad, that would not imply that these sins are equally bad. This section will explore why that is the case.

Naively, one can appeal to standard transfinite (cardinal) arithmetic to defend the view that all infinite sins are equally bad. One way to “measure” infinity is to map it to the size of the set of an infinite series of numbers. For example, there are an infinite number of natural numbers, {1,2,3…}. By convention, if you count the number of numbers in this set (i.e. the “cardinality” of the set of natural numbers), you get the number ℵ0 (pronounced “aleph-zero” or “aleph-naught”).

In transfinite arithmetic, adding or subtracting finite numbers to an infinite number like ℵ0 does not change its value. Thus, ℵ0 + 5 = ℵ0 – 27 = ℵ0 + 1,356,874 = ℵ0 (see Wolfram Alpha’s computation of this and play with the numbers, if you wish). In fact, even multiplying ℵ0 by nonzero numbers does not change its value. ℵ0 x 54 = ℵ0 x 999,999,999 = ℵ0. This is because the set of natural numbers can incorporate any finite (or countably infinite) number of additional members and each member still be put into a 1-to-1 correspondence with the set of natural numbers (or the set of integers or the set of rational numbers), and thus has identical size (cardinality). Therefore, someone may say, the way in which sins are worse or better, which must be finite differences in nature, do not make any difference to their ultimate evil, which remains . So, all sins are equally evil.

There are two problems with this: the first is mathematical and the second is moral. There are actually two mathematical disputes one can have with the aforementioned reasoning. The first is that ℵ0 is not the only infinite number, but it is merely the smallest infinite number. There are an infinite number of infinite numbers, each larger than the last. One can obtain ever larger infinite numbers by taking the power set of the previous set, starting with the set of natural numbers (or the integers). The power set of set S is the set that contains all subsets of set S (which would include the empty/null set ∅. For example, consider the set S = {1,2,3}. The subsets would include the empty set, each individual member, each group of two, and the group of three. So, the power set P(S)={∅,1,2,3,{1,2},{1,3},{2,3},{1,2,3}} . As you can see, the power set is much larger than the original set, and this difference would only increase as you increase the size of the set. In fact, there is a proof called Cantor’s theorem that the cardinality of the power set is strictly larger than the cardinality of the original set. The relevant implication is that taking the power set of the natural numbers would produce a much larger set (with cardinality 2ℵ0 > ℵ0)[21] than the set of natural numbers itself. Therefore, sins could potentially have very different levels of badness if they corresponded to different transfinite numbers, whether ℵ0, ℵ1, ℵ2, ℵ3 … ℵn. Perhaps, however, if God has a value of ℵ1, all sins would be evil of level ℵ1, but this is questionable.[22]

Figure 3: A picture I took of Cantor’s paradise of the different sizes of infinities approaching heaven.

The second mathematical dispute is that transfinite ordinal arithmetic, unlike transfinite cardinal arithmetic, does allow straightforwardly for comparisons among sizes of infinity even with finite differences. Ordinal numbers are those numbers like “first”, “second”, “third,” etc., that indicate ordering (larger/smaller or higher/lower than), whereas cardinal numbers are those that measure the size of sets. Usually, the smallest infinite ordinal number is termed ω, and in transfinite ordinal arithmetic, the following comparisons are correct: ω2 > 2ω > ω + 5 > ω. So, if the badness of infinite sins can be faithfully represented as transfinite ordinal numbers, which I would have every reason to think so, then not all infinite sins are equally bad. I won’t get into this further, as I think this kind of reasoning leads naturally to the moral objection to not being able to make infinite comparisons.

Now, let us move to the moral objection. If there are such things as infinitely bad actions, then, plausibly, this could entirely break ethics (at least, assuming certain things that I find obviously true, such as an aggregation principle). The good news is that, unlike Christian ethicists who have largely ignored this problem (although they even more than consequentialists need to reckon with this problem that arises from the infinite value of the afterlife), consequentialists have worked substantially on the question of comparing worlds that involve infinite value.

While I would love to get into the messy details of how this may work,[23] I really think the only thing you need to see is that it is incredibly obvious that some infinite evil is less bad than other infinite evil. For example, Oliver Crisp provides a comparison of two people, Trevor and Gary, consigned to eternal hell, “Both suffer an infinite punishment in hell. But Trevor is only punished for one hour a day whereas Gary is punished for twelve hours a day. Clearly, in this state of affairs they are both punished infinitely but not equally. Therefore, an [Infinite Punishment] does not entail an [Equal Punishment].”[24] An eternity of daily suffering to degree n+1 is worse than an eternity of daily suffering to degree n. One does not need to merely appeal to the naïve quantitative sum of evil in transfinite cardinal arithmetic in order to make reasonable moral evaluations.

If humans are infinitely valuable, then one must also consider the implications for a status principle when applied to wronging humans. One of those implications is that, obviously, some wrong actions against beings of infinite status are worse than others. For example, slapping my friend is morally better than chopping his finger off, all else equal. If all sins against infinitely valuable beings are equally bad, then sins against other humans are all equally bad, which is clearly incorrect. In fact, this reasoning suggests that not all sins against beings of infinite value are even infinitely evil, as most minor wrongdoings against humans are clearly only finitely valuable. We can give a similar parity argument about good actions against this kind of status principle (see the end of the Scriptural Support for the Inequality of Sins section below for more). Further, lying against humans seems to be exactly one such case of a finite sin, even if it is done against a being of infinite value (humans). Therefore, there is some reason to suspect that lying against a different infinite being (God) would similarly be of finite disvalue.[25]

Clearly, even granting that a sin is infinite, we do not get the conclusion that the sin is just as bad as another infinite sin. The relevant takeaway is that lying may be infinitely bad and yet, since is presumably less bad than killing, killing still not be a justified punishment due to lack of proportionality.

But can we even get to the idea that all sin against God, including lying, is infinitely bad? Next, we must investigate this aspect of the Status Principle.

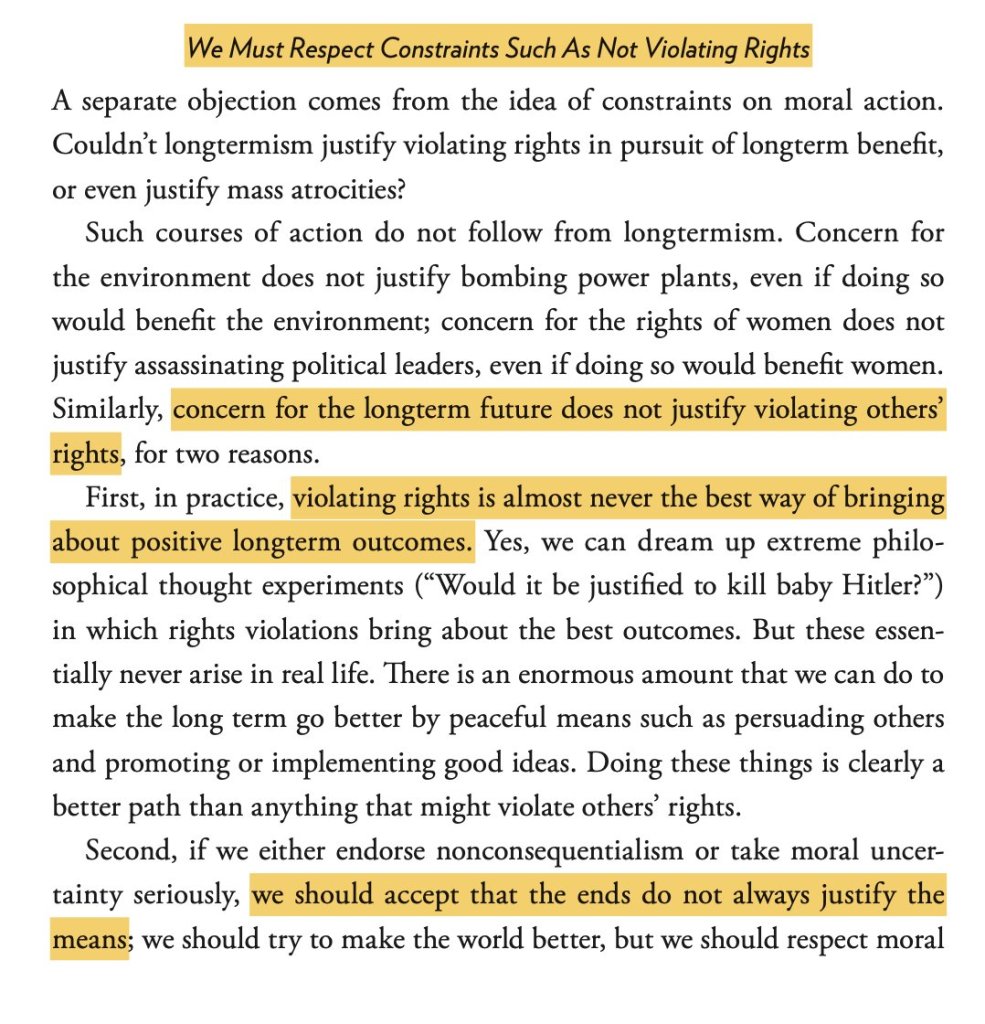

Finite Sins Against Infinite Beings

As I stated previously, the debate about infinite sins is usually in the context of debating the justification of an eternal hell. This makes sense, as any defense that a sin is infinitely bad would amount to a justification for eternal hell (assuming retributivism). If killing humans is infinitely bad, then hell is justified for killing humans. If lying by itself is sufficient for eternal hell, then lying is infinitely bad, and vice versa.[26] Yet, to many people, telling one lie does not seem sufficient for eternal damnation. So, if a status principle entails that lying is infinitely bad, then so much for that status principle; it should be rejected.

What exactly is the Status Principle? One rendering is,

Status Principle: Other things being equal, the higher the status of the offended party the worse the act of the offender, and the greater the guilt of the offender.[27]

One kind of example people appeal to is an interhuman example, such as saying that slapping Ghandi is worse than slapping a heinous criminal. An even more obvious case, which is more relevant by appealing to the very different “statuses” of the actors in question, killing a human is much worse than killing a pig (and that is in virtue of the difference in moral status or worth). I think some version of this principle seems very plausible.

The most plausible version of the Status Principle (SP) is going to be a version that does not settle the question of the badness of the wrongdoing with merely the status of the offended alone. So, premise (3), which says the badness of an act is principally determined by the wronged’s worth/dignity, needs to be replaced with a more plausible status principle. The key contemporary defenders of the status principle do just that, combining the relevance of the status of the offended with some kind of intrinsic magnitude of the wrongdoing, and the badness of the action is proportional to both of these things.

For example, Crisp words his SP as, “for any person who commits a sin, the guilt accruing for that sin leading to punishment is proportional to both, (a) the severity of the actual or intended harm to the person or object concerned, and (b) the kind of being against whom the wrong is committed.”[28] The specifics of (a) are such that it is subject to numerous objections on the widespread applicability of either actual or intended harm, but I think these can plausibly be adapted to be widely appealing, including discussion of dishonor rather than just harm, and even considering the possibility of God experiencing infinite dishonor or infinite harm.[29]

The real takeaway from this discussion so far is that the most plausible status principle does not guarantee an entailment that all sins are infinitely bad, but only some sins. This is true because while all sins against God are against an infinite being, all sins are not infinite in the (actual or intended) harm or dishonor they cause God. For example, Francis Howard-Snyder states that “one needn’t argue that all sin is equally deserving of the ultimate punishment in order to argue that all sinners are equally deserving. All one needs to argue is that there is a class of sins (‘mortal sins,’ perhaps) such that we’ve all committed at least one member of this class and that one of them is enough to qualify one for [eternal hell].”[30] I lean toward the view that there is only one such sin that actually deserves eternal hell, which is the intentional rejection of the infinite good of God and a relationship with Him.[31]

So, taming a status principle to allow for both finite and infinite sins against an infinitely worthy being is certainly the more plausible way to go, and I have yet to see any argument for the view that lying would specifically be one of those sins against God that would be infinitely bad. As we saw earlier, it would make a lot more sense of sins against humans that lying would generally be a finitely bad sin, and I see no reason to think would change when lying to God (especially if humans are infinitely valuable).

Therefore, I conclude that endorsing a status principle does not give any reason to think that the sin against God of lying is infinitely bad. In that case, I see no reason to think that, for general reasons, killing would be a proportionate response to lying.

Responses to Some Arguments for the Equality of Sins

Sometimes I have heard[32] Christians (including my past self) say phrases like “all sin is equally sin” or “all sin is equally wrong” or that “all sin is equally worthy of damnation.” These may be true on a technicality (and I now probably think the last phrase is just incorrect), but I think they are best avoided, as they are at best misleading and tautological. I suspect that the use of these and related phrases betray an improper appreciation of the varying magnitudes of sin, but this lack of appreciation is sourced in a good desire and motivation to emphasize just how awful all sin is, and how opposed God is to sin of any kind, which often goes insufficiently appreciated.

“All Sin is Equally Sin”

All sin is sin. This is true because sin is sin, by definition. Trivially, all x’s are x’s, in virtue of being an x. Saying that it is “equally” an x adds nothing to that sentence. So, yes, it is true that each sinful action is equally a sinful action or equally just as much fulfilling the criterion of being a sinful action, in virtue of it being a sinful action. That’s not what anyone cares about or means when they ask about if sins are equal. “All sin is equally sin” is a trivial tautology that tells us nothing about the nature of sin or its badness. Thus, it is probably best to avoid using this phrase.

“All Sin is Equally Wrong”

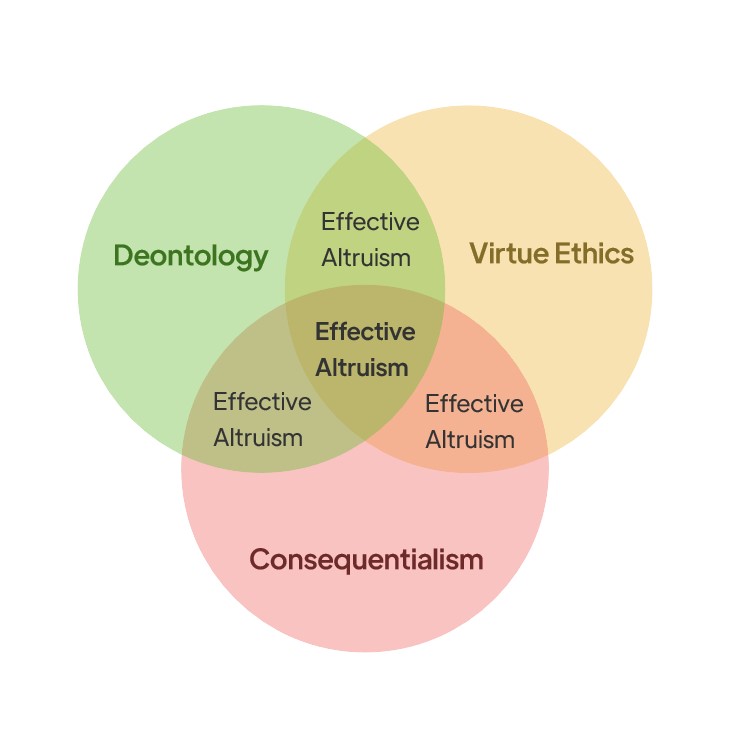

Since sin is identical to moral wrongdoing, all sins are morally wrong actions. Since, because all sins fit the criteria of being morally wrong, by definition, then all sins are “equally” morally wrong because there is no way for things to be “unequally” morally wrong, as that does not even make sense. Contrary to what my ethics professor argues, moral wrongness does not come in degrees, as it is a binary option. An action is either wrong or it is not. In standard ethics, there is a threefold classification of actions: an action is either obligatory, optional, or impermissible (wrong). Consequentialism,[33] which is the correct moral theory, simplifies things further to only two categories: obligatory and impermissible. If an action is obligatory and you fail to do it, it is impermissible (wrong). If an action is permissible, then you do nothing wrong. As long as you are not obligated to do not-x, then doing x is permissible (i.e., not wrong).

What does come in degrees is how evil a morally wrong action is, which is exactly what people are actually getting at when talking about the equality of sins. Some wrong actions are better or worse than other wrong actions. In other words, while all sin is morally wrong, different wrongdoings have different magnitudes. Since the magnitude of the wrongdoing is what people are actually talking about when asking if all sin is equal, to say that all sin is equally morally wrong is, at best, misleading.

The fact that there are different magnitudes of moral wrongdoing is obvious considering what it means to do wrong. What it means to do wrong is to do anything but the best option from your list of available actions.[34] The list of actions available to you is a function of time, and it might be that you find yourself in a (pseudo[35]-)moral dilemma such that all the possible actions are evil, in which case the least evil action is right and all others are wrong. Alternatively, if you have the opportunity to save 1000 people, and you only save 999, you have done something wrong, but you have still done something really good (and clearly something better than killing all 1000 people, which is “just as wrong” but way worse). Moral right and wrong are distinct from moral good and bad, as right actions can still have negative results or be negative intrinsically, and thus be a morally evil action, while wrong actions can be very good and even revolutionize society for the better, and still be wrong because it was not the best you could do.[36]

“All Sin Deserves Hell (Infinite Punishment)”

Sometimes, Christians will emphasize that it only takes a single sin to, in short, send people to hell. They may say that only one sin, any sin, is sufficient for eternal damnation. I think I used to believe this, but I am currently skeptical of this, or at least it requires some finagling to work. I do believe that a single sin is sufficient to make you unable to enter into the fullness of God’s presence, lest you be destroyed, due to God’s maximal perfection and holiness. If it is true that one sin disqualifies you from heaven, and hell just is the total absence of God’s presence and nothing more, then it appears as though one sin, any sin, is sufficient for damnation. However, it is not true that any sin guarantees infinite or eternal damnation, as we saw earlier with the status principle discussion. In this case, it seems annihilation is the best option.[37]

While I think the most defensible view is that only a subset of sins, or perhaps a single sin (the unforgiveable sin), would be justification for eternal damnation, I want to explore one way in which any sin might be sufficient to justify eternal damnation. Consider an idealistic case of a non-Christian that has heard and understands the Gospel and has heard reasonable versions of arguments for Christianity. The idea is that each and every sin is going to implicitly accompanied by an ongoing sin in the background, which is the rejection of a relationship with the one true God and a refusal to repent for that sin. For a Christian, each and every sin has forgiveness associated with it and thus while damnation may be warranted, it is not imposed. On the other hand, the unrepentant sinner has, in association with each and every sin, a lack of repentance to the almighty God of the universe and a rejection of the greatest gift of all, a relationship with God. If this lack of repentance and relationship wasn’t there (i.e., if there was repentance and relationship), then this sin would be forgiven and damnation would not be imposed (and plausibly not warranted based on the status principle discussion, i.e., if nothing infinitely bad is done).

However, I think a key part of this idea is that it is a sin itself to have this lingering background rejection of repentance and relationship, a sin that is distinct from any other given sin of lying, adultery, etc. If so, then it is really just this sin of rejecting the Gospel that is what warrants eternal damnation, not any given sin of lying or whatever. Therefore, it sounds a bit weird to say that all sin deserves eternal damnation, when it is really one particular sin that deserves it.

We can take the case to its limits to test this idea: consider two non-Christians, one whom has only sinned once (except for rejecting the Gospel) in their life, by telling a lie when they were 16 to their parents that they were going to study for an exam when they were actually going to hang out with friends. The other non-Christian has never sinned in any specific instance other than their rejection of the Gospel.[38] My suggestion here is that if it is the case that both these non-Christians warrant eternal punishment, the lie has absolutely nothing to do with that. It could only plausibly be the rejection of the Gospel that could bear the weight of justifying eternal damnation. The only reason that the first non-Christian warrants infinite punishment is because of the accompanying sin of rejecting God’s infinitely great gift and Himself, and not because of the lie. Therefore, I doubt it is the case that any sin warrants infinite punishment.

So, the only way that it would be true that any sin warrants infinite punishment is only in case we assume that sin entails this other background sin of the rejection of the Gospel and God Himself. If that is true, I again think it is misleading to say that all sin warrants infinite punishment. It would be all sin (with their associated and background entailments) warrants infinite punishment, and such that the associated background entailments are really what warrant infinite punishment.

One final note is not quite an argument about equality of sin as much as it is an argument about God’s response to sin. Some Christians will say that God created us, he can do literally whatever he wants with us, and it be perfectly justified for God to strike someone dead for basically no reason whatsoever. This represents a “He brought you into this world, He can take you out” mentality. I think this is plainly incorrect, except on a super uninteresting gloss of the word “can.” The best interpretation or version of this argument, in its strongest form and with additional assumptions, concludes that God does not have moral obligations toward us, not that God would be justified to act in any possible way towards us (just as parents cannot abuse their children just because they brought them into this world). This still does not imply that God can do anything to us in any interesting sense. It is still the case that, since God is morally good and perfect and all-loving, that God would act in certain ways, respect us and acting in line with our wellbeing, etc., even if, technically, it is not true that God should act in those ways. It is for this reason that God’s lack of obligations does not defeat the problem of evil, as divine obligations or their lack is in fact completely irrelevant for making evidential assessments of how God would act. The point is: God merely being creator of Ananias and Sapphira does not imply that God is automatically justified in striking them dead. That’s just not how ethics works, including God’s Own Ethics.

Scripture on the (In)equality of Sins

Some Christians might say that while all sin is not equal in our flawed human eyes, all sin is equal in God’s eyes, and we should trust Him and His omniscient nature over our own. So, in this section, we will look at Scripture to see what the Bible has to say about whether all sins are equal.

Scriptural Support for the Equality of Sins

The Wages of Sin is Death (Romans 6:23)

One may appeal to Romans 6:23 in support of the equality of sins. Romans 6:23 says that “the wages of sin is death.” One way to read this verse in support of saying all sins are equal is reading this verse as implying that “the wages of each and every sin is death.” The “death” here is commonly understood as referring to spiritual death, which usually translates to “eternal hell” for evangelicals, something I won’t dispute here.

The first problem with this reading is that appears to be opposed to 1 John 5:16-17, which distinguishes between a kind of sin that leads to death, and a kind of sin that does not lead to death. 1 John 5:17 reads, “All wrongdoing is sin, but there is sin that does not lead to death.” The normal interpretation of this verse appears to be that the sin that does not lead to death is a sin from which one repents. This understanding aligns nicely with my proposal earlier, which is that it is unrepentance that leads to spiritual death. Therefore, the kind of sin that will actually result in spiritual death is that accompanied by unrepentance (and thus a rejection of God’s offer of forgiveness). Finally, even if one is able to conclude that Romans 6:23 implies that every sin deserves eternal hell, as we saw earlier, hell has gradings of punishment, and some eternal punishments are worse than others, so not all sins are equal simply in virtue of deserving eternal punishment. Therefore, Romans 6 cannot imply that all sins are equal in God’s eyes.

The best response to 1 John 5 might be to say that while Romans 6 is talking about wages, about what one deserves, while 1 John 5 is talking about what actually happens, and one may not get what one deserves just in case one repents, so what sin deserves and what sin leads to may come apart. That is the whole basis of the Gospel after all, that sinners do not get what they deserve when they repent. However, an obvious reason a sin may not lead to death is if it does not actually deserve death (since God is just and acts in accordance with what is warranted). So, 1 John 5:17 could be understood to teach that not all sins warrant spiritual death (e.g., if it is repented of), which is why it will not lead to death. Therefore, 1 John 5:17 gives some reason to read Romans 6:23 to be referring to sin generally and not each and every sin individually. Further, I still stand by the claim about levels of eternal hell as being sufficient to block this argument.

In addition, I will point out that the verse does not say “the wages of each and every sin is death,” but just that “the wages of sin is death.” It makes sense to understand this comment to be about sin in general, which is always accompanied, in the relevant cases, by unrepentance, if it is going to be the kind of sin that deserves damnation. So, my earlier discussion for why I don’t think it is true that all sin warrants eternal hell is one reason to not read Romans 6:23 in this “each and every” way.

In conclusion, I do not think Romans 6:23 gives any reason to think all sin is equal in God’s eyes.

Sins of Thought vs Sins of the Body (Matthew 5)

The next Scripture people may appeal to support the idea that all sin is equal in God’s eyes is Jesus’ teaching in the Sermon on the Mount, particularly Matthew 5:21-22 (murder) and 5:27-28 (adultery). The idea here is that Jesus connects sins of the heart (in your thoughts) with sins of the body (in your actions), so that lust is adultery and hate/anger is murder. Therefore, the argument goes, having thoughts of adultery is identical in its badness to committing adultery (with the body).

This is not a good argument, for multiple reasons. First, let us look at what Jesus actually taught. Jesus states the uncontroversial claim that “anyone who murders will be subject to judgment,” followed immediately with, “But I tell you that anyone who is angry with a brother or sister will be subject to judgment.” First, let us go ahead and clarify that the kind of anger in question is not the justified kind of righteous anger Jesus espouses and supports elsewhere, but an inappropriate kind of anger. So, Jesus clearly thinks that anger can be sinful. But note what Jesus does not say.

What Jesus says is that murder will be subject to judgment, and that anger will be subject to judgment. He does not say that anger will be subject to the same judgment that murder will be. Jesus’ teaching is perfectly compatible with anger being subject to a less severe judgment than murder, even if anger is subject to a severe judgment that his audience would not have expected.

Similarly, Jesus says that “anyone who says, ‘You fool!’ will be in danger of the fire of hell.” This statement says nothing about the expected amount of punishment in hell being equal to killing someone. In fact, since he does not say “eternal hell,” we cannot without argument conclude that calling someone a fool warrants infinite punishment.[39] The statement suggests that insults warrant punishment, but it doesn’t say anything about deserving the same amount of punishment as killing someone. It is only through reading the text with a preconfigured lens that we would come away with that conclusion.

Figure 4: An authentic 1st century photograph of Jesus arguing with the Jewish religious leaders about lust and adultery.

The same analysis is true regarding Jesus’ comments about adultery. Jesus quotes the commandment “You shall not commit adultery,” followed by “But I tell you that anyone who looks at a woman lustfully has already committed adultery with her in his heart.” It just doesn’t follow from that statement that committing adultery in your heart is just as bad as committing adultery with your body. Jesus designates it as, at minimum a distinct subcategory, which is adultery “of the heart”, different from the distinct subcategory, “of the body.” Nothing in his statement precludes these two distinct subcategories from having different levels of badness, even if they both are, without hesitation, wrong.

In fact, even within one of these subcategories, sins of the body, there are clearly levels of badness. Not all adultery (of the body) is the same. Kissing an unmarried woman once while mildly intoxicated is not as morally bad as a full-on affair for months. The fact that lust is in the category of adultery (of the heart) does not mean lusting for a woman after a bad day once in your life is as bad as cheating on your wife with a different woman every week for 3 decades. Jesus’ innovation to the typical 1st century ethic was that these sins of the mind and heart are sins at all, not that these two subcategories are of equal badness.

That, I think, is the main point: Jesus was correcting a Pharisaic tendency to ignore sins of thought completely. Jesus and Paul both continuously corrected the idea that it is not what goes into or out of the body that defiles the person, but these actions are the natural outcomes of a corrupt heart (Matthew 15:17-20, Mark 7:20-23). So, Jesus was teaching that there are, in fact, sins that occur solely in the mind. The idea that sins of thought were a legitimate category of sins at all was foreign to the Pharisees, and Jesus was correcting their sole focus on external traditions as being the basis for evaluating one’s righteousness.

Here is what I think is happening, or here is one way of analyzing this argument that I think makes clear how it goes astray: Sometimes, when making this argument, Christians will say that all sin is the same in God’s eyes, but some sins have worse consequences than others, are more disastrous for interpersonal relations, etc. In other words, we might distinguish between the “intrinsic” disvalue of some action and its “instrumental” disvalue (i.e., negative consequences that it leads to). So, these people would say that adultery of the heart has the same intrinsic disvalue of the adultery of the body, but adultery of the body has more negative consequences; as Paul says, unlike other sins, sexual sins are “sins against their own body” (1 Corinthians 6:18).[40]

Let’s grant that sins of thought have the same intrinsic disvalue as sins of the body (i.e., externally carrying out one’s thoughts of murder, adultery, etc.). The fact that they differ in their instrumental disvalue just is to say that some sins are worse than others! Differentiating sins (or any instance of moral value of an action, good or bad) includes the sum of both intrinsic and instrumental value. This is explicitly built into consequentialism, but any plausible moral theory includes known consequences to some degree in the moral evaluation of the goodness or badness of an action.

Consider the following two hypothetical scenarios, and let us judge the moral badness of these two actions.

Option 1: you shoot someone, and they fall down and die.

Option 2: you shoot someone, and they fall back onto a big red button that launches nuclear missiles to every square meter on earth, killing all human civilization, and you knew this would happen before you shot them.

Which one of these actions is morally worse, or are they morally equal? Obviously, the second action is morally much worse than the first one, despite shooting someone having equal intrinsic disvalue in both scenarios. Therefore, consequences factor into moral evaluation of actions, so saying that sins are “equal in God’s eyes” but differ in consequences doesn’t make any sense.

In summary, we have no reason to think that Jesus’ teachings on sins of thought on lust and anger of the heart implied these are just as bad as committing physical adultery or killing, respectively. I believe it is admirable that Christians want to take sins of thought so seriously, and this is something well-deserved. God hates sin, include sins of thought. Sins of thought are also likely to lead to sins of the body. As Paul said, it is essential for us to “take captive every thought to make it obedient to Christ” (2 Corinthians 10:5). Sins of thought detour our relationship with God and need to be repented of. If we ever find ourselves dismissing our sinful thoughts as “well, it’s better than actually doing it,” then we are in need of correction and mortification of the flesh, which includes putting these fleshly thoughts to death. All of this we can affirm while still recognizing that some sins are worse than others, and we do not need to throw away these clear moral intuitions if we don’t need to in order to align with Scripture.

Guilty of One = Guilty of All (James 2:10)

I saved what is perhaps the most difficult challenge for last. James 2:10 says, “For whoever keeps the whole law and yet stumbles in one point, he has become guilty of all.” At first glance, this might imply that all sins are equal because if you break one commandment, you become guilty of breaking every commandment. At second glance, however, I believe the point is that the law is taken as a whole, not in individual parts, and so, for the purposes of this passage, comparison between individual sins cannot be done in either direction, whether to establish equality or inequality.

The point in James 2 appears to be emphasizing the categorical or qualitative change that takes place when moves from the category of sinless to sinful, from innocent to transgressor. James 2:9 picks out an individual sin, the sin of partiality (as opposed to love), and says that committing this sin means you “are convicted by the law as transgressors.” It is relevant that “the law” is taken as a whole. You are a transgressor of “the law,” not “the command to love.” So, James 2 isn’t thinking about the badness of individual sins at all.

Similarly, James 2:11 says that, even though the law includes commands against both adultery and murder, “If you do not commit adultery but do murder, you have become transgressor of the law.” Again, “the law” is holistic and categorical. Committing one sin is sufficient to move you from the category of righteous, pure, sinless to the category of sinful, unrighteous, and in need of repentance, forgiveness, and mercy in order to ever be in the fullness of God’s presence again.

In other words, in terms of your need for a Savior, committing one sin makes it so (in a sense) you might as well have committed them all, as you won’t make it to heaven unless you repent and trust in Christ as your Savior. The person who has committed 147,000 sins is equally in need of a Savior as the person who has committed 4 sins, which is to say that every sinner is fully, 100% in need of a Savior. It is recognition of this point that every sinner is on equal ground before the Savior: we all are completely and categorically at God’s mercy for saving. Thankfully, “mercy triumphs over judgment” (James 2:13). So, we can affirm wholeheartedly the point of the verse, that any sin makes one 100% in need of a Savior, while making room for the difference in badness of individual sins.

I think Barnes’ Commentary is worth quoting at length here on the meaning of “he is guilty of all” in James 2:10 that explicitly defends differences of sin in the face of this verse:

He is guilty of violating the law as a whole, or of violating the law of God as such; he has rendered it impossible that he should be justified and saved by the law. This does not affirm that he is as guilty as if he had violated every law of God; or that all sinners are of equal grade because all have violated some one or more of the laws of God; but the meaning is, that he is guilty of violating the law of God as such; he shows that be has not the true spirit of obedience; he has exposed himself to the penalty of the law, and made it impossible now to be saved by it. His acts of obedience in other respects, no matter how many, will not screen him from the charge of being a violator of the law, or from its penalty.

I conclude that James 2:10 is about the equality of each sinner in need of a Savior having crossed from the category of sinless to sinner in virtue of only one sin, and that different magnitudes of sin is compatible with the teaching in James 2.

Scriptural Support for the Inequality of Sins

Unlike the Scriptural support for the equality of sins, there are many more than three verses or groups of verses that support different magnitudes of sin. Let’s start in the Old Testament.

Old Testament

First, we can see different magnitudes of sin reflected in the punishments in Old Testament law. Since punishment should be proportional to the magnitude of the moral wrongdoing for justice to be met, and God instituted the punishments in the OT in line with his justice, then different punishments in OT law reflect a difference in moral magnitude of sins. This is true even assuming we can differentiate a tripartite law of ceremonial, moral, and civil law.

For example, Numbers 15 describes offerings for unintentional sins, such as a goat for a sin offering, contrasting that with someone who sins “defiantly,” whose punishment involves being cut off from the people of Israel. Both of these differ from various other sins, such as violating the Sabbath, which invoke the death penalty.

In a different way, Proverbs 6:16-19 singles out “six things the LORD hates; seven that are detestable to him,” suggesting these might be of particular disinterest to God compared to other sins. Lamentations 4:6 says, “For the wrongdoing of the daughter of my people is greater than the sin of Sodom.”[41] This sounds like a very straightforward proclamation that some wrongdoing has higher magnitude than others.

The Old Testament affirms the concept of ultimate justice in Psalm 62:12 and Proverbs 24:12 (and probably many other verses that I have not yet collected). Proverbs 24:12 rhetorically asks, “Will he not repay everyone according to what they have done?” and Psalm 62:12 says of God, “You reward everyone according to what they have done.” This concept of justice suggests that punishment will be based on one’s works. I think it is assumed here that these works are differentiated in magnitude (just as OT law punishments are differentiated in magnitude), but see the New Testament section for more discussion.

New Testament

The New Testament even more clearly indicates a difference in the magnitude of wrongdoing of different sins. When Jesus sent out his disciples, he said that for towns that reject them, “it will be more bearable for Sodom and Gomorrah on the day of judgment than for that town” (Matthew 10:15). In this next chapter, this is immediately applied to the cities of Chorazin and Bethsaida, stating that “it will be more bearable for Tyre and Sidon on the day of judgment than for you” (Matthew 11:22), and then to Capernaum, saying that “it will be more bearable for Sodom on the day of judgment than for you” (Matthew 11:24). If some cities will be better off on judgment day, then that means their punishment will be less, and thus their wrongdoing was less in magnitude.

Jesus, in a parable where God is the master and we are the servants, teaches that “The servant who knows the master’s will and does not get ready or does not do what the master wants will be beaten with many blows. But the one who does not know and does things deserving punishment will be beaten with few blows” (Luke 12:47). This suggests that intentional sin is worse than unintentional sin given a difference in proportional punishment, in agreement with the OT teaching above.

Jesus told Pilate that “the one who handed me over to you is guilty of a greater sin” (John 19:11), which is about the most explicit statement of some sins being better or worse than others as you can possibly get. If that doesn’t imply that not all sins are equal, I don’t know what does. James 3:1 comments that “Not many of you should become teachers, my fellow believers, because you know that we who teach will be judged more strictly,” implying that a teacher doing a wrong action is worse than a non-teacher doing the same wrong action, presumably because by doing so, he would lead more than just himself astray.

Plausibly, Jesus singling out a specific sin of “whoever causes one of these little ones who believe in me to sin”, saying that “it would be better for him to have a great millstone fastened around his neck and to be drowned in the depth of the sea” (Matthew 18:6) suggests that this sin is worthy of a uniquely bad punishment, worse than other sins. If the claim was true of every sin, then Jesus would merely be repeating himself (and this seems independently implausible). Presumably, Jesus is making a point that is only true of a subset of sins, ones that are deserving of being drowned in response rather than committing this sin.

Like the Old Testament, the New Testament affirms ultimate justice, which presumes that sin is differentiated. Many verses claim that God “will judge/repay/reward each person according to their deeds/works.” This statement is found in Matthew 16:27, Romans 2:6, Revelation 2:23, and Revelation 22:12, and comparable claims are found in 1 Corinthians 3:13 and probably others. Assuming authorial intent guides our interpretation, we must consider how the audience would have understood the meaning of these passages. Since the audience was ordinary people without bizarre moral intuitions, they likely would have understood and believed that repayment according to one’s works implies different magnitudes of punishment. I think this is decent reason for us to accept there are different magnitudes of punishment, and thus different magnitudes of wrongdoing. If repayment according to one’s works actually meant everyone got the same punishment, a standard amount consistent across all people (which would in essence be independent of the vast majority of one’s works), then was I would instead expect a reference to “the ultimate punishment” or something like that in the place of every instance of “repayment according to their works.”

Finally, we see different magnitudes of rewards in the NT, so, all else equal, I would expect to see different magnitudes of punishments. 2 Corinthians 5:10 says, “For we must all appear before the judgment seat of Christ, so that each one may receive what is due for what he has done in the body, whether good or evil.” This verse sets up a parity between good and evil in the receiving one’s due at the judgment. Verses talk about particular rewards, such as a crown of glory for shepherding God’s flock (1 Peter 5:2-4) or a crown of life for persevering under trials or martyrdom (James 1:12, Revelation 2:10), and these suggest that not all good actions will get the same reward. Similarly, Jesus in Mark 10:29-30 teaches that those who have “left house or brothers or sisters or mother or father or children or lands, for my sake and for the gospel” will receive rewards a hundredfold, both now in this life “and in the age to come.” Since I would expect the repayment for good and bad to be on a par, as suggested by 2 Corinthians 5:10, then the presence of differentiated magnitudes of rewards implies the presence of differentiated magnitudes of wrongdoing.

In fact, this parity between good and evil actions suggests a parity argument against the equal magnitude of sins based the status principle. The status principle analysis above focuses only on wrongdoing, but what about the equivalent principle for good actions? If every action of disobedience against an infinite being is infinitely bad, then I would think that every action of obedience is infinitely good. However, clearly, not every action of obedience is infinitely good (and therefore deserving of infinite reward, aka heaven). The New Testament seems to designate particular good actions as deserving certain rewards that not all will get, and further these seem like finite rewards. Both of these facts are at least prima facie incompatible with a seemingly equally justified status principle about the goodness of obedient actions or other acts of goodness toward an infinite being (e.g., hugging another human). So, this parity gives us reason to doubt the implication that all wrongs against an infinite being are infinitely or equally bad.

Contextual Specificities (Why Ananias and Sapphira are Special)

In the previous section, we saw that, on general grounds, we have no reason to think that killing is a proportionate punishment for lying. I suppose to the average non-evangelical, we could have taken this as our starting point, but I wanted to explore and rule out some claims I have somewhat commonly, but certainly not universally, heard from evangelicals about all sins being equal.

If killing is not a proportionate punishment for lying, then something else must be going on; Ananias and Sapphira must be a case of particular circumstances that make them special that would make God justified in killing A&S for lying, if God would be justified at all.

There is some reason to suspect special circumstances from the outset, as it is not normally the case that lying is immediately met with death in Scripture. For example, Abraham lying to Pharoah that his wife is his sister to, Joseph’s brothers deceived Jacob about Joseph’s death, Laban tricks Jacob about giving his daughter in marriage and the serpent lied to Eve. None of these people were struck dead for their sin of deception. Although we know generally that God does not always meter out punishment immediately when deserved, as he is merciful and relents many times, we still have some limited reason to think there may be something special happening here, unique to the context of the 1st century church, since it is so rarely the case that we (or others in Scripture) die immediately upon telling a lie.

The Finite Case

One proposal that I find reasonable is that, in the beginning stages of the early church, the church needed to be very carefully and exquisitely pruned to set up the rest of the church’s future for success (this idea was mentioned by one of my Bible study members and also discussed here). It would be essential to protect the church from sins that could destroy church unity or undermine church trust, if its members were regularly engaging in any kind of deception toward one another. The New Testament emphasizes so heavily the unity of the church that any challenge to it needed to be shown much seriousness. The live possibility of deception by any given church member would undermine this trust and unity.

Therefore, God striking down Ananias and Sapphira can serve to emphasize this importance of trust and ruling out deception among the church body. This could help solidify the opposition to sin and God’s hatred of wrongdoing into the hearts of the early church. Acts even records the success of this effect, saying that “great fear seized the whole church and all who heard about these events” (Acts 5:5,11). This effect would be a reduction of sin, as living in the fear of God tends to do that.

Figure 5: Source

God was beginning a new stage of His relationship with His people, so it was important to swiftly enact justice to set a principle and example, as the early church was in its infant stages. This event seems similar to the stoning of Achan when he held back some of the treasures in the conquest for himself, whenever Israel was finally able to enter the Promised Land, entering into a new stage of the divine-Israel relationship. Further, the recording of this event in Scripture guarantees that this example would be set in stone for the ages, so all future generations could learn from it and appreciate this same importance of honesty, trust, and hatred against sin. Thus, this one event likely prevented many future sins from occurring and was probably justified if killing a person is only finitely valuable.

The Infinite Case

But even if this makes sense, we haven’t obviously made sense of the killing of Ananias and Sapphira if killing is infinitely disvaluable. The infinite value of humans is likely going to swamp our moral calculus. This means that if someone is killed, the only way to justify this action is by saving human lives or changing someone’s trajectory from hell to heaven, not just preventing some finite sum of finite sins.

I propose that the event of Ananias and Sapphira, as well as its recording in Scripture, has or will eventually cumulatively result in saving at least two human lives, whether in the physical or spiritual sense. One such mechanism is a greater appreciation of the fear of God and hatred of sin decreases the chance that one finds themselves of the character (cumulative effects of right/wrongdoing) that would result in someone being killed or let die in a careless way. This only needs to happen for 1 or 2 people throughout the past 2,000 years or however many years until Jesus returns in order for this passage to make sense, morally. That doesn’t seem unreasonable to me.

Alternatively, the character improvement from having the example of Ananias and Sapphira in history and Scripture is likely to make us less sinful, better influences on others, and for Christianity to be more attractive to others, which makes it more likely for people to get saved. This last step is essentially the application of the meager moral fruits argument (which doesn’t require the argument to be sound, but only convincing to non-Christians). Since many people are turned off from Christianity due to hypocrisy or other moral failings, and A&S leads to less hypocrisy and other moral failings, fewer people will be turned off from Christianity. Therefore, the event of A&S likely will lead to more people being in heaven than would otherwise be. Thus, A&S is justified.