Summary

Effective altruism (EA) has been in the news recently following the crash of a cryptocurrency exchange and trading firm, the head of which was publicly connected to EA. The highly-publicized event resulted in several articles arguing that EA is incorrect or morally problematic because EA increases the probability of a similar scandal, or that EA implies the ends justify the means, or that EA is inherently utilitarian, or that EA can be used to justify anything. In this post, I will demonstrate the failures of these arguments and others that have been amassed. Instead, there is not much we can conclude about EA as an intellectual project or a moral framework because of this cryptocurrency scandal. EA remains a defensible and powerful tool for good and framework for assessing charitable donations and career choices.

Note: This is a long post, so feel free to skip around to the sections of particular interest using the linked section headers below. Additionally, this post is available as a PDF or Word document.

- Summary

- Introduction

- Effective Altruism Revealed

- My Background

- SBF Association Argument Against Effective Altruism

- Genetic Utilitarian Arguments Against Effective Altruism

- Do the Ends Justify the Means?

- Effective Altruism is Not Inherently Utilitarian

- Can EA/Consequentialism/Longtermism be Used to Justify Anything?

- Takeaways and Conclusion

- Post-Script

- Endnotes

Introduction

Recently, there has been a serious scandal primarily involving Sam Bankman-Fried (SBF) and his cryptocurrency exchange FTX, precipitating a crash of billions of dollars into bankruptcy. I am talking about this because SBF has been publicly connected to the effective altruism movement, including being upheld as a good example of “earning to give,” which is where people purposely take lucrative jobs in order to donate even more money to effective charities. For example, Oliver Yeung took a job at Google and is able to donate 85% of his six-figure income to charities while living in New York City; for four years, he lived in a van to push this up to 90-95% of his income.

SBF met William MacAskill, one of the leaders and founders of the effective altruism (EA) movement, in undergrad, and MacAskill convinced him to go into finance to “earn to give.” SBF did very well, working at a top quantitative trading firm, Jane Street, and he decided to work with some other effective altruists (EAs) to start a trading firm Alameda Research and eventually a cryptocurrency exchange FTX that was intimately connected with Alameda. FTX and Alameda were doing really well, ballooning in the past several years. At his peak, right before the downfall, SBF had a net worth of $26 billion.

Like many other cryptocurrency exchanges, FTX produced its own altcoin, FTT, which gives some discounts and rewards to customers and acts as stock, and SBF had some of his company’s own assets in FTT. Trouble started in early November when CoinDesk published an article expressing concern over Alameda’s balance sheet, revealing an unhealthy amount of assets invested in FTT, which is essentially its own made-up currency. FTT-related assets amounted to over $6 billion assets of Alameda’s $14 billion assets, leaving Alameda extremely vulnerable to sudden drops in investment due to their limited ability to liquidate enough assets to pay the sellers.

Unfortunately for SBF, the Binance CEO decided to sell all of Binance’s FTT tokens, collectively worth $529 million. The CEO also publicly announced the sale, triggering a bank-run where many other customers decided to sell their FTT and withdraw their funds from FTX entirely. As a result of the run, $6 billion was withdrawn from FTX within 72 hours. FTX did not have the liquid assets to cover all of this and rapidly collapsed, declaring bankruptcy.

It became apparent that the investments of Alameda were extremely risky, even though they repeatedly told customers they have loans with “no downside” and high returns with “no risk.” It was revealed that Alameda’s risky bets were made with customer deposits, which is apparently a big “no-no”. As far as I can tell, it is not clear whether SBF actually committed fraud, but he clearly mishandled funds and misled customers about their funds, possibly in a way that violated the business’s terms and conditions.

In the fallout of this disaster, which included the closing of over 100 other organizations and the loss of many employees’ life savings, etc., effective altruism came under fire for their connection to SBF. SBF, was, after all, following suggestions given by EA organizations when he decided to “earn to give.” Further, he has explicitly advocated for EA-adjacent reasoning in maximizing expected value, though he also champions a more risk-tolerant approach than EAs tend to prefer.

The question everyone is asking (and most are poorly answering) is: “Is effective altruism to be blamed for SBF’s behavior?”

Many articles in popular media have denounced effective altruism in the wake of the crash, characterizing the philanthropic approach as “morally bankrupt,” “ineffective altruism,” and “defective altruism.” They say the FTX scandal “is more than a black eye for EA,” “killed EA,” or “casts a pall on [EA].” Articles linking the scandal and EA, most of them critical of EA, have been published in the New York Times, the Guardian, the Washington Post, New York Magazine, the Economist, MIT Technology Review, Philanthropy Daily, Slate, the New Republic, and many other sites.

In this post, I am going to subject these articles and their arguments to scrutiny to see what exactly we can conclude about EA’s framework of evaluating the effectiveness of charities and careers and how they advocate for why and how we should do so in the first place. In short, my answer is: not much. There is not much we can conclude about EA from the FTX scandal.

I am only going to be investigating in search of critiques and assessing the articles as critiques of effective altruism. Some of these articles might have additional or entirely different purposes but sound sufficiently negative toward EA that I will nonetheless assess whether we can construct an argument against EA as a result.

Furthermore, I want EA to be criticized in the same sense that, for any given position, I want the best arguments and evidence for and against each side to be raised and assessed in the most rigorous way. Of course, that doesn’t mean every argument is equally good. I have spent much time looking at academic critiques of effective altruism, which I (normally) find more compelling, as they are more rigorous. However, most recent online criticisms are just not good.

In this post, I will 1) give a precise characterization of effective altruism, 2) mention possibly relevant background information that informs my perspective in evaluating EA, 3) address what seems to be the most frequent concern, yet to my mind remains the most perplexing concern, that SBF’s association with EA reveals that EA has an incorrect framework, 4) respond to arguments against EA that rely on the utilitarian origins of EA or its leadership, 5) clarify “ends justify the means” reasoning in recent discourse and normative ethics more broadly, 6) introduce six differences between EA and utilitarianism, showing that is EA independent of any commitments to consequentialism, and, finally, 7) respond to the concern that EA or consequentialism or longtermism can be used to justify anything and is therefore incorrect. With each argument, I try to reconstruct what is the best version of the critique against EA, since much of the argumentative work in these articles is left implicit or neglected entirely.

I welcome responses, better reconstructed arguments, corrections, challenges, counter-arguments, etc. Let’s dive in.

Effective Altruism Revealed

In “The Definition of Effective Altruism,”[1] William MacAskill characterizes effective altruism with two parts, an intellectual project (or research field) and a practical project (or social movement). Effective altruism is:

- the use of evidence and careful reasoning to work out how to maximize the good with a given unit of resources…

- the use of the findings from (1) to try to improve the world.

We could perhaps summarize this to say that someone is an effective altruist only if they try to maximize the good with their resources, particularly with respect to charitable donations and career choice, since that is EA’s emphases. A few features of this definition that MacAskill emphasizes are that it is: non-normative, maximizing, science-aligned, and tentatively impartial and welfarist.

We can further distinguish between different kinds of effective altruists[2]: normative EAs think that charitable donations that maximize good are morally obligatory, and radical EAs think that one is morally obligated to donate a substantial portion of one’s surplus income to charity. Normative, radical EAs combine these two together, and I independently argue for normative, radical EA in a draft paper (see n. 2). It is helpful to distinguish these kinds of EAs (minimal, normative, radical, or normative radical), where the summary of MacAskill’s definition is considered the minimal definition that constitutes the core of effective altruism, while the normative and radical commitments are auxiliary hypotheses of effective altruism. I will revisit this in the Effective Altruism is Not Inherently Utilitarian section.

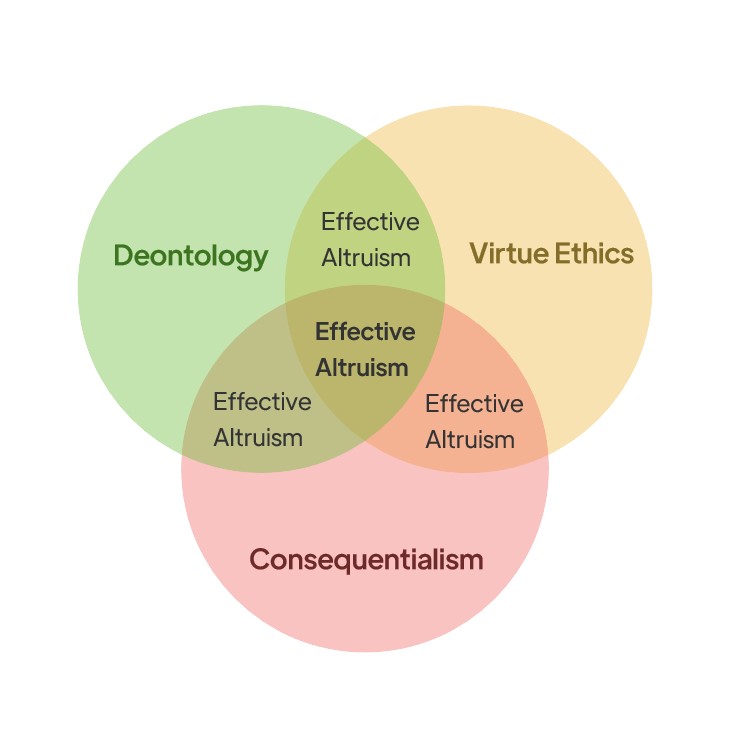

Based on the characterization above, we can quickly dispel two key errors that articles repeatedly made. One error is that “effective altruism requires utilitarianism” (then “utilitarianism is false”, concluding “EA is incorrect”). The truth is that utilitarianism (trivially) implies effective altruism, but effective altruism does not imply utilitarianism. In fact, I would put effective altruism at the center of the Venn diagram of the three moral theories (see Figure 1). There are strong deontological and virtue ethical arguments to be made for effective altruism. See Effective Altruism is Not Inherently Utilitarian section for more on this, including one theory-independent and two virtue ethical arguments for EA. Also, see this 80,000 Hours Podcast episode on deontological motivations for EA.

The second important flawed criticism is that longtermism is an essential part of effective altruism. The core commitments of effective altruism do not imply longtermism, and longtermism does not require effective altruism. Instead, longtermism is an auxiliary hypothesis of EA. Longtermism could be false while EA is correct, and EA could be false while longtermism is correct. To get from EA to longtermism, you need an additional premise that “the best use of one’s resources should be put towards affecting the far future,” which longtermists defend, but EAs can reasonably reject. EA is committed to cause neutrality, so it is open to those who think non-longtermist causes should be prioritized.

As we will see, many people writing articles with criticisms of effective altruism could really stand to read the FAQ page on effectivealtruism.org, as many of the objections have been replied to at-length (not to mention academic level pieces), including the difference between EA and utilitarianism or neglecting systematic change. Another, slightly more advanced, but more precise discussion on characterizing effective altruism is in the chapter “The Definition of Effective Altruism” by MacAskill. The very first topic MacAskill covers in the “Misunderstandings of effective altruism” section is “Effective altruism is just utilitarianism.”

My Background

I call myself an effective altruist. I think that effective altruism is obviously correct with solid arguments in its favor. It follows from very simple assumptions, such as i) it is always permissible to do the morally best thing,[3] ii) acting on strong evidence is better than acting on weak evidence, iii) if you can help someone in great need without sacrificing anything of moral significance, you should do so, etc. If you care about helping people, you are spending money on things you don’t need, and you don’t have infinite money, then you might as well give to where it helps the most. This just makes sense. On the other hand, I wouldn’t call myself a longtermist[4] (regarding either weak longtermism that says affecting the longterm future is a key moral priority or strong longtermism that says it is the most important moral priority), as I am skeptical about many of their claims. I simultaneously think most critiques I have heard of longtermism (I have not read much, if any, academic work on this) are lacking.

I have known about effective altruism since early 2021 and took the Giving What We Can pledge in March 2021. However, I was convinced of its way of thinking for several years, since early in undergrad. I have mostly been a part of Effective Altruism for Christians (EACH) more than the broader EA movement. I have not worked for an EA organization directly and do not have a local EA group to be a part of. I had never even heard of Sam Bankman-Fried until this whole scandal happened, though I heard other people talking about the FTX Future Fund (but I didn’t know what FTX was).

The closest to an “insider look” I have gotten into EA as an institutional structure is conversations with some people at an EACH retreat in San Francisco, one of which worked for an EA startup and started an EA city chapter. The other has been involved in the EA Berkeley community. Some of the things they said suggested that there are ways that various EA suborganizations could be further optimized in their use of funding, but nothing super concerning.

I will be mostly looking at recent pieces insofar as they contribute to the debate about the intellectual project and moral framework of EA, as I find that to be the most interesting, important, and fundamental questions at hand. The end result of this inquiry has direct bearing on whether we should give to EA-recommended charities like GiveWell, rather than asking e.g., whether the Center for Effective Altruism should spend less on advertising EA books, which is a different question entirely and not central to the EA project. Additionally, I have engaged with enough material on the moral frameworks in question (and normative ethics more broadly) to hopefully have something to contribute to evaluating the EA moral framework .

SBF Association Argument Against Effective Altruism

A lot of recent critiques of EA appeared to have the general outline of the form:

- Sam Bankman-Fried (SBF) engaged in extremely problematic practices.

- SBF was an EA/was intimately connected to EA/was a leader of EA.

- Therefore, EA is a bad or incorrect framework.

(1) is uncontroversial. On (2), SBF was clearly connected in a very public way to EA. The extent to which he was following or internalized EA principles can be challenged, and I will also question in inference from (1) and (2) to (3). What exactly is the argument from SBF’s actions and connection to EA to concluding that EA is either inherently or practically problematic?

Was SBF Acting in Alignment with EA?

The most relevant question in this whole debacle is that whether the EA framework implies that SBF acted in a morally permissible manner. The answer is this: it is extremely unlikely that, given the EA framework, what SBF did was morally permissible.

EA leaders have repeatedly repudiated the general type of scenario that SBF engaged in numerous times. In fact, William MacAskill and Benjamin Todd give financial fraud as a go-to example of what would be an impermissible career choice on an EA framework. Eric Levitz in the Intelligencer acknowledges this by saying that “MacAskill and Todd’s go-to example of an impermissible career is ‘a banker who commits fraud.’” Eric says that MacAskill and Todd specifically argue that “engaging in harmful economic activity to generate funds for charity probably is .” Additionally, “they suggest that performing a socially destructive job for the sake of bankrolling effective altruism is liable to fail on its own terms.”

It is very difficult to see how a virtually guaranteed bankruptcy, when thousands of people are depending on you for their lifesavings, jobs, and altruistic projects, is actually the best moral choice. Fraud is just a bad idea and is completely independent of effective altruism. The disagreement here may merely be on the empirical question rather than the moral question (it is notoriously difficult, at times, to separate empirical from moral disagreement, as empirical disagreement is often disguised as moral disagreement).

MacAskill calls out SBF’s behavior as not aligned with EA: “For years, the EA community has emphasised the importance of integrity, honesty, and the respect of common-sense moral constraints. If customer funds were misused, then Sam did not listen; he must have thought he was above such considerations.” Furthermore, “if he lied and misused customer funds he betrayed me, just as he betrayed his customers, his employees, his investors, & the communities he was a part of.”

Additionally, his practices were just clearly horrible financially. He misplaced $8 billion dollars. John J. Ray III, who oversaw the restructuring of Enron and is now overseeing FTX, said about the FTX financial situation, “Never in my career have I seen such a complete failure of corporate controls and such a complete absence of trustworthy financial information as occurred here. From compromised systems integrity and faulty regulatory oversight abroad, to the concentration of control in the hands of a very small group of inexperienced, unsophisticated and potentially compromised individuals, this situation is unprecedented.” These practices obviously do not give a maximum expected value on any plausible view.

SBF Denies Adhering to EA?

In addition, Sam Bankman-Fried himself appeared to deny that he was actually attempting to implement an EA framework, though he later clarified his comments were about crypto regulation rather than EA. Nitasha Tiku in The Washington Post (non-paywalled) puts it as, “[SBF] denied he was ever truly an adherent [of EA] and suggested that his much-discussed ethical persona was essentially a scam.” Tiku is referring to an interview between SBF and Kelsey Piper in Vox. Piper interviewed SBF sometime in the summer, where SBF said that doing bad for the greater good does not work because of the risk of doing more harm than good as well as the 2nd order effects. Piper asked if he still thought that, to which he replied, “Man all the dumb sh*t I said. It’s not true, not really.”

When asked if that was just a front, as a PR answer rather than reality, to which he said, “everyone goes around pretending that perception reflects reality. It doesn’t.” He also said that most of the ethics stuff was a front, not all of it, but a lot of it, since it’s just about winners and losers on the balance sheet in the end. When asked about him being good at frequently talking about ethics, he said, “I had to be. It’s what reputations are made of, to some extent…I feel bad for those who get f—ed by it, by this dumb game we woke Westerners play where we say all the right shiboleths [sic] and so everyone likes us.” He said later, though, that the reference to the “dumb game we woke Westerners play” is to social responsibility and environmental, social, and governance (ESG) criteria for crypto investment rather than effective altruism.

Perhaps the most pessimistic and antagonistic of people would say, perhaps as Tiku did, that SBF only said what he did to protect EA. The idea is that he actually was an effective altruist, believed it, but lied about it just being a front in order to help save face for EA. Tiku says that EA’s brand “helped deflect the kind of scrutiny that might otherwise greet an executive who got rich quick in an unregulated offshore industry,” also reflected in the title of the article, “The do-gooder movement that shielded Sam Bankman-Fried from scrutiny.” Since we do not have access to SBF’s mental states, I do not care to speculate much about his reasoning for saying what he said. Armchair psychoanalysis is not exactly a reliable methodology.

People argue about whether or not SBF was being truthful here or not. He appeared to believe he was speaking off the air, suggesting honesty. If so, then he did not believe he was actively trying to implement the EA framework (unless SBF’s answers about his ethics in the Vox interview were intended to be disconnected from the EA framework and solely about regulations, which to me is not clear either way but didn’t seem entirely disconnected). Ultimately, I do not think much hinges on whether SBF believed he was implementing the EA framework, since it is more important whether or not SBF’s actions are a reflection of what is inherent in the EA framework, which they are not.

Now, I have little interest in attempting to disown SBF because he is now a black sheep. There is no doubt that EA painted SBF as a paradigm case of an actor doing great moral good by using his money to invest in and donate to charity. We EAs have to own that, and EAs got it incorrect due to our lack of knowledge about what was happening behind the scenes. Could there have been more to be done to prevent this from happening? Probably, and EAs are taking this very seriously, doing a lot of soul searching. It is likely there will be more safeguards put into place. These are reasonable questions, but they have little to do with the moral framework of EA itself, since the EA framework still ends up rendering SBF’s gamble as impermissible.

Next, I will investigate whether or not the mere connection between SBF and EA, rather than an alignment between EA’s framework and SBF’s actions, is sufficient to challenge EA’s framework.

EA is Not Tainted by SBF

Now that we know SBF’s actions do not coincide with EA principles, we can investigate how the connection between SBF and EA could be used as an argument against EA. Recent articles mostly seem to just toss the two names next to each other in an obscure way without making any clear argument, hoping that one will be tainted by the other.

An Irrelevant “Peculiar” Connection

For example, Jonathan Hannah in Philanthropy Daily says, “MacAskill claims to be an ethicist concerned with the most disadvantaged in the world, and so it seems peculiar that he was inextricably linked to Bankman-Fried and FTX given that FTX claimed to make money by trading cryptocurrencies, an activity that carries serious negative environmental consequences and may play a role in human trafficking.” The environmental consequences have to do with crypto mining that uses a lot of electricity (more than some countries as a whole), and the role in human trafficking is that virtual currencies are harder to track, so they are frequently used in black market activities.

It is hard to understate how much of a stretch this argument is. Here is an equivalent argument against myself (relevant background is that I studied chemical engineering at Texas A&M, which also has a strong petroleum engineering program). I say I care about the disadvantaged, yet I have many friends that went into the oil and gas industry (and some of them listened to my suggestions about charitable donations). Oil and gas bad. Curious! Further, I have many more friends that love, watch, and/or attend football and other public sporting events, and yet these events are associated with an increase in human trafficking.[5] Therefore…I don’t care about the disadvantaged? And therefore my thoughts (or knowledge of evidence like randomized control trials) about helping others are wrong? Looks not much better than Figure 2.

Of course, effective altruists have spent a great deal of time working on the issue of weighing the moral costs and benefits of working in plausibly harmful industries vs working for charities. This isn’t exactly their first rodeo. See 80,000 Hours: Find a Fulfilling Career That Does Good and Doing Good Better: Effective Altruism and How You Can Make a Difference (you can get a free copy of either of these at 80,000 Hours). We can also quickly consider SBF’s scenario (I am only considering my first-glance personal thoughts, and not attempting to use the 80,000 Hours framework). In SBF’s case, he has earned enough money from cryptocurrency to carbon offset all the cryptocurrency greenhouse emissions in all of the U.S. many times over.[6] Additionally, it is hard to see why employees (or employers) of cryptocurrency can be blamed for human trafficking purchases with crypto, especially no more than the U.S. treasury can be blamed for human trafficking purchases done with cash (which seems negligible at best). Plus, many other things he can do with the remaining sum not spent on carbon offsetting, resulting in a net good (especially compared to what other job opportunities he could take, many of which have comparable negative effects).

Skills in Charity Evaluation ≠ Skills in Fraud Detection in Friends

The same author also asks, “If these ‘experts’ failed to see what appears to be outright fraud committed by someone they were close to, why should we look to these utilitarians to learn how to be effective with our philanthropy?” This is again a strange conditional. Admittedly, I have not had many friends that committed billions of dollars’ worth of fraud (perhaps the author has more experience), but I would not expect them to go to their close friends and say, “Hey I’m committing fraud with billions of dollars, what do you think?” Acts like those done by SBF are done in desperation with a sinking ship, like a mouse backed into a corner, or someone with a gambling habit (especially apropos for the given situation). You get deeper into debt, take more risks, assuming and desperately hoping that it will work out in the next round. Repeat until bankruptcy. This is not something you go telling all your friends about (instead, you lie and try to siphon money from them, as was recently done by a Twitch scammer).

In addition, the skills and techniques it takes to assess the effectiveness of charities are quite different from the skills it takes to discover that your friend is committing massive fraud with his business. So, the reason we should look to EAs to be effective in philanthropy is because they have good evidence for charity effectiveness. Randomized control trials (or other comparable methods) are not exactly the tools optimized for detecting fraud in friends’ businesses.

Now, was there nothing suspicious about SBF prior to this point? No. There was some reason for suspicion. And of course, hindsight is 20-20. They evidently attempted to evaluate SBF and his ethical approach in 2018. I’m unsure the details of this, and I don’t know how much changed in SBF’s behavior in 4 years. As I mentioned earlier, like the desperation of a gambler, the risks and bad behavior likely exponentially increased over time leading to the present failure. Thus, we would expect most of the negative behavior to be heavily weighted towards 2022 rather than 2018 when he was reviewed. This debacle will likely increase scrutiny into this type of behavior (as much as possible across organizational lines), and with good reason. I won’t say EA as an organization or community is blameless here. But that doesn’t change the EA framework as being the best (and correct) framework for evaluation of charity effectiveness.

Without making this connection more explicit, this looks like a fallacious argument; however, like all informal fallacies, there is likely a reasonable argument form in the vicinity. Let us try to consider some of these possibilities.

EA Does Not Problematically Increase the Risk of Wrongdoing

Here is one way of putting the key inference for this argument: if something increases the probability of believing or doing something wrong, then it is bad or incorrect (and EA does this, so EA is incorrect). Of course, this is implausible, as then we couldn’t do anything (re: MacAskill’s paralysis argument). If we always had to minimize the probability of engaging in wrongdoing (through violating constraints) or false beliefs, then we should do (or believe) nothing.[7] This is one standard argument for global skepticism. If the only epistemic value is minimizing false beliefs, then having zero beliefs would ensure you have the minimum number of false beliefs, which is zero. This approach is clearly incorrect, since we do have knowledge and it is permissible to get out of bed in the morning.

Here’s another reductio: becoming a deontologist increases the probability that you will believe that we have a deontological requirement to punch every stranger we see in the face, since consequentialism does not include deontological requirements while deontology does, so deontologists need to put higher credence in variants of deontology. However, this is an implausible view that no one defends, so this mild increase in probability is uninteresting at best.

A second, more plausible version of the inference for this argument is: if something substantially increases the probability of believing or doing something wrong, then it is bad or incorrect (and EA does this, so EA is incorrect). Random on Twitter seems to suggest something like this in response to Peter Singer’s (too) brief article when he identified the criticism as being that EA is “a philosophy that tends to lead practitioners to believe the ends justify the means when that’s not the case.” In any case, this is an extremely difficult and unwieldy claim to deal with at all, as this empirical premise is quite difficult to substantiate. First of all, increases the probability compared to what? What is the base rate for how frequently someone does the relevant wrong in question? And what is the probability given one is an EA? Do we only compare billionaires? Do we compare millionaires and beyond? Do we only compare SBF to other crypto businessmen?

In the absence of a more clear and substantiated argument, it is hard to see how this argument can be successful. Maybe we can ask, of the people that we know made incorrect assessments of ends vs means and thought the ends sometimes justifies the mean, what percent of them accept the EA framework? Good luck with that investigation. Plus, we are inevitably going to end up doing armchair psychoanalysis, a notoriously unreliable method.

Furthermore, there is another response. Plausibly, a framework can substantially increase the probability of people doing something wrong, and yet the framework entails that we should not do that thing. In such a case, it is hard to see why the framework goes in the trash if it gives the correct results even if in practice people’s attempted implementation end up doing the wrong thing.

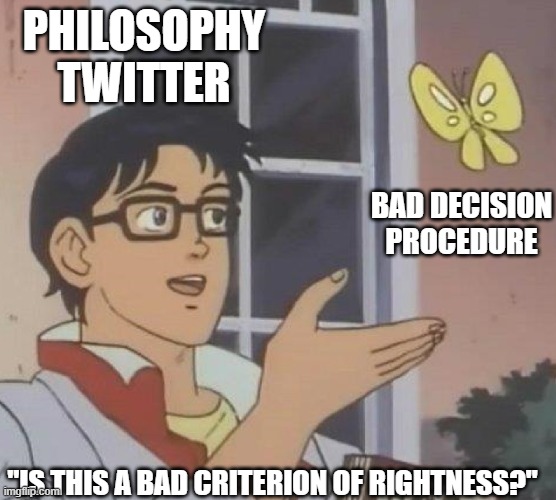

To see this, consider is the difference between a criterion of rightness, which is how we evaluate and conclude if an action is morally right or wrong (as a 3rd party), and a decision-making procedure, which is the method an agent consciously implements when deciding what to do. This is a standard distinction in normative ethics that diffuses various kinds of objections, especially having to do with improper motivations for action. It may be that the decision procedure that was implemented is wrong, but this does not show that the normative or radical EA’s criterion of rightness is incorrect. I suspect that Richard Chappell’s meme about this distinction is actually a reference to this (or a closely related) mistake, since his other tweets and blog posts around the same time are referring to similar errors in commentary on EA and the FTX scandal (such as this thread on a possible connection between guilt-by-association arguments and inability to distinguish criterion of rightness and decision procedure).

In summary, to answer Eric Levitz’s question “Did Sam Bankman-Fried corrupt effective altruism, or did effective altruism corrupt Sam Bankman-Fried?”, the answer is “Neither.” SBF did not act in a way aligned with EA, whether he thought he was or not. Until a better argument is forthcoming that SBF’s incorrect approach implies that EA’s framework is flawed, I conclude very little about the EA framework.

The EA framework is well-motivated, even on non-consequentialist grounds (as we will see later), and EA is an excellent way to help others through your charitable donations and career. To the extent that the FTX scandal makes EA look bad, it is only because of improper reasoning. There are likely additional institutional enhancements that can be implemented as protections against these kinds of disasters, but my intent here was to investigate the EA framework more than the EA practice in all of its institutional details, to which I am not privy. Therefore, I can conclude that the EA framework is correct and unmoved by the SBF and FTX scandal.

Genetic Utilitarian Arguments Against Effective Altruism

There is another set of claims I will assess in these critical articles related to effective altruism’s connection to utilitarianism in the form of historical and intellectual origins. Inevitably, especially from opponents of utilitarianism, any connection to utilitarianism is deemed hazardous and not to be touched with a ten-foot pole. For example, I have had several Christian friends be terrified of effective altruism because they hear that Peter Singer is connected to it.[8]

Genetic Personal Argument Against EA

I can briefly consider this genetic personal argument against EA. The best version of the principle in question to make an inference against EA is probably something like, “if a person is wrong about the majority of claims you have heard from that person, then the prior probability of the person being right about a new claim is fairly low.” The principle should likely be restricted to the claims that you have heard from that person that you got from a source including many more of that person’s beliefs and even arguments for said position. Otherwise, you risk making inferences from an exaggerated source, and the principle would be false. Even then, the principle would only tell you the prior probability. You need to update your background knowledge with further evidence to get the posterior probability of any given claim, so it remains important to actually investigate the person’s reasons for believing the new claim before making a definitive judgment on the new claim. Therefore, EA cannot be dismissed on a personal basis without assessing the arguments for EA, such as those referenced in the independent motivation section.

Genetic Precursor Argument Against EA

There may be another genetic argument raised against EA, which is that “the historical and intellectual precursors to EA involved utilitarian commitments, and so EA is inextricably linked to utilitarianism. Further, utilitarianism is false, and therefore EA is false.” I will examine each part of this argument in turn.

First, we need to examine the factual basis of the historical and intellectual connection between EA and utilitarianism in the first place. A number of recent critical articles point out the genetics of the EA tradition. I think facts about this connection are worth pointing out; yet it is important to clarify the contingent nature of this linkage, especially given how despised utilitarianism is to the average person. If this clarification was neglected as a kind of “poisoning the well” or “guilt by association”, shame on the author, though I do not make that assumption.

The Economist (non-paywalled) writes, “The [EA] movement…took inspiration from the utilitarian ethics of Peter Singer.” It would be more accurate to say that “the movement took inspiration from arguments using common sense intuitions from Peter Singer, and Peter Singer is a utilitarian.” Of course, that’s much less zingy to acknowledge that the arguments from Singer inspiring EA were not utilitarian in nature (from his “Famine, Affluence, and Morality”), as we discuss with more detail in the utilitarian-independent motivation subsection of Effective Altruism is Not Inherently Utilitarian section.

Rebecca Ackermann in Slate writes, “The [EA] concept stemmed from applied ethics and utilitarianism, and was supported by tech entrepreneurs like Moskovitz.” This is just a strangely worded sentence. It would make more sense to say it stemmed from arguments in applied ethics, but applied ethics is merely a field of inquiry. Moreover, utilitarianism is a moral theory. So, you could say it is an implication of utilitarianism, but proposing that EA stemmed from a moral theory is a bit weird. That’s mostly nit-picking, and I also have absolutely no idea what the support from tech entrepreneurs has to do with anything. I guess the “technology” audience cares? Other articles appear to poison the well against EA merely by saying rich tech billionaires support EA, as though everything tech billionaires support is automatically incorrect, though this article may not be attempting to make such a faulty ‘argument’.

Rebecca Ackermann in MIT Technology Review writes “EA’s philosophical genes came from Peter Singer’s brand of utilitarianism and Oxford philosopher Nick Bostrom’s investigations into potential threats to humanity.” Similar to above, the ‘genes’ of utilitarianism are connected in the person of Peter Singer but not in the arguments of Peter Singer, which is an incredibly important distinction. EA does not rely on his brand of utilitarianism, and it is important to clarify this non-reliance to the public that wants to throw up anytime the word “utilitarianism” is mentioned. Also, Bostrom’s existential risks aren’t even a core part of EA; they are a more recent development. From my perspective, this development is much less of the genes of EA (though Bostrom was writing about longtermism- and extinction-related topics before EA) and more of a grafting into EA, at least as far as how much weight or significance the existential risks have.

Now, it is quite possible that the authors of these articles were merely noting the historical roots of the movement, which is of perfectly legitimate interest to note. Given that the average person finds utilitarianism detestable, however, suggests that it would be important for neutrality’s sake to clarify that effective altruism is not, in fact, wedded to the exact beliefs of the originators or even the current leaders.

If this connection was made to critique EA, this amounts to a kind of genetic argument against effective altruism. Whether these authors were attempting this approach (implicitly) is not my primary concern, and I will not comment either way, but since this is a fairly popular type of argument to make, I will investigate it. In fact, it does seem like the general structure of recent critiques of EA due to SBF and FTX are a guilt by association argument, which I explored in the SBF Association Argument Against Effective Altruism. My best attempted reconstruction of the genetic utilitarian argument is of the form:

- If the originators and/or leaders of a movement espouse a view, then the movement ineliminably is committed to that view

- The originators and/or leaders of the EA movement espouse utilitarianism

- Therefore, the EA movement is ineliminably committed to utilitarianism

- If a movement is ineliminably committed to a false view, then the movement has an incorrect framework

- Utilitarianism is false

- The EA movement has an incorrect framework

A Movement’s Commitments are not Dictated by the Belief Set of Its Leaders

One problem with this argument is that premise (1) is obviously false. Regarding the originators, movements can change. Additionally, leaders have many beliefs 1) unrelated to the movement, and 2) even related beliefs may not imply nor be implications of the framework. This can be true even if the originators and leaders all share some set of views P1 = {p1,p2,p3…p7}, as the movement may be characterized by a subset of those views P2 = {p1,p2}, where P2 does not imply {p3…p7}. This is likely the case in the effective altruism movement, as P2 does not encapsulate an entire global moral structure and so does not imply the entirety of the leader’s related views. Further, there can be a common cause of the beliefs of the leaders that are non-identical to the common cause of the beliefs of the core of the movement.

Another way to remit the concern above is to consider the core of the theory vs auxiliary hypotheses, as discussed in philosophy of science. If P2 is the core of effective altruism, it can be true that beliefs in P1, that are not in P2, are auxiliary hypotheses but can still be freely rejected by those in the movement and remain true to EA.

There is a parallel in Christianity as well. There is substantial diversity in the movement that is Christianity, yet there is a common core of essential commitments of Christianity, called “essential doctrine”. These commitments constitute the core of the theory of Christian theism. Beyond that, we can have reasonable disagreements as brothers and sisters in Christ. As 7th century theologian Rupertus Meldenius said, “In Essentials Unity, In Non-Essentials Liberty, In All Things Charity.”

This disagreement extends from laymen to pastors and “leaders” of the faith as well. I think this should be fairly obvious for people that have spent much time in Christian bubbles. Laymen can and do disagree with pastors of their own denomination, pastors of other denominations, the early church fathers, etc., and they remain Christian without rejecting essential doctrine. (Of course, some church leaders and laymen are better than others at not calling everyone else heretics).

EA Leaders are Not All Utilitarians

The second point of contention with this argument is that premise (2) is also false. William MacAskill can rightly be called both an originator and a leader of EA, and he does not espouse utilitarianism. He thinks that sometimes it is better to not do what results in the overall greatest moral good. He builds in side-constraints (though sophisticated forms of utilitarianism can do a limited version of this, and consequentialism can do precisely this in effect). Furthermore, he builds in uncertainty in the form of a risk-averse expected utility function with distributed credences between (at least) utilitarianism and deontology, which motivates side-constraints.

In this section, we examined two arguments against effective altruism in view of its connection to utilitarianism, finding both arguments substantially lacking. In conclusion from the previous two sections, we do not see a successful argument against effective altruism due to its theoretical or historical connection to utilitarianism. EA remains a highly defensible intellectual project.

Do the Ends Justify the Means?

There is a need for clarity around “ends-justifying-means” reasoning and claims like “the end doesn’t justify the means.” Many recent criticisms make this claim in response to the FTX scandal. They connect effective altruism to what they see as “ends-justifying-means” reasoning in Sam Bankman-Fried (SBF) and use that as a reductio against effective altruism.

This argument fails on virtually every point.

First, let’s see what people have said about it. Eric Levitz in the Intelligencer says that “the SBF saga spotlights the philosophy’s greatest liabilities. Effective altruism invites ‘ends justify the means’ reasoning, no matter how loudly EAs disavow such logic.” Eric also writes, “Effective altruists’ insistence on the supreme importance of consequences invites the impression that they would countenance any means for achieving a righteous end. But EAs have long disavowed that position.” Rebecca Ackermann in Slate mentions, “EA needs a clear story that rejects ends-justifying-means approaches,” referencing Dustin Moskovitz’s Tweets.

As the authors above mention, EA thinkers typically, on paper at least, disavow “ends justify the means” reasoning. More recently, MacAskill in a recent Twitter thread says, “A clear-thinking EA should strongly oppose ‘ends justify the means’ reasoning.” Holden Karnofsky, co-founder of Open Philanthropy and GiveWell, in a recent forum post says, “I dislike ‘end justify the means’-type reasoning.” This explicit rejection is not solely in the wake of the downfall of FTX; MacAskill 2019 in “The Definition of Effective Altruism” says, “as suggested in the guiding principles, there is a strong community norm against ‘ends justify the means’ reasoning.”[9] I talk more substantively about the use of side constraints in EA in the 4th difference between EA and utilitarianism below.

Of course, critics of EA readily acknowledge that EA, on paper, disavows ends-means reasoning. The problem, they think, is that EA “invites” ends-means reasoning, or that EA “invites the impression that they would countenance any means for achieving a righteous end” over and against EA’s claims.

All of the above discussion fails to acknowledge two very key points, which is due to the ambiguity in what “ends justify the means,” in fact, means. These two points become obvious once we adequately explore ends-means reasoning[10]; they are: (1) some ends justify some means, and (2) “ends justify the means” is a problem for every plausible moral theory.

Some Ends Justify Some Means

Obviously, some ends justify some means. Let’s say I strongly desire an ice cream cone and consuming it would make me very happy for the rest of the day with no negative results. Call me crazy, but I submit to you that this end (i.e., Ice Cream) justifies the means of giving $1 to the cashier. If this is correct, then some ends justify[11] some means. Therefore, it is false that “the end never justifies the means.”

Various ethicists have pointed this out. Joseph Fletcher says that people “take an action for a purpose, to bring about some end or ends. Indeed, to act aimlessly is aberrant and evidence of either mental or emotional illness.”[12] Though, it may be that this description in line with the “Standard Story” of Action in action theory entails a teleological conception of reasons that has distorted debates in normative ethics in favor of consequentialism, as Paul Hurley has argued.[13]

Nonetheless, Fletcher is right that even this commonsense thinking on everyday justification for any action “leads one to wonder how so many people may say so piously, ‘The end cannot justify the means.’ Such a result stems from a misinterpretation of the fundamental question concerning the relationship between ends and means. The proper question is – ‘Will any end justify any means?’ – and the necessary reply is negative.”[14] It is obviously false that any end justifies any means, and everyone in the debate accepts that, including the hardcore utilitarian.

What happens when we raise the stakes of either the end or the means?

Some Ends Justify Trivially Negative Means

We can consider raising the moral significance of the end in question. Let us consider the end of preventing the U.S. from launching nuclear missiles at every other country on the globe (i.e., Nuclear Strike). Although lying is generally not morally good, I submit that it is morally permissible to fill in your birthday incorrectly on your Facebook account if it prevents Nuclear Strike. An end of great moral magnitude like Nuclear Strike justifies a mildly negative means like a single instance of deception on a relatively unimportant issue. Therefore, a very good moral end justifies a mildly negative means.

Similarly, when James Sterba considers the Pauline Principle that we should not do evil so that good may come of it, he acknowledges it is “rejected as an absolute principle…because there clearly seem to be exceptions to it.” Sterba gives two seemingly obvious cases where doing evil so that good may come “is justified when the resulting evil or harm is: (1) trivial (e.g., as in the case of stepping on someone’s foot to get out of a crowded subway) or (2) easily reparable (e.g., as in the case of lying to a temporarily depressed friend to keep him from committing suicide).”[15]

No End Can Justify Any Means

Further, there is no end that can justify any means. For any given end, we can consider means that are way worse. For example, consider the end of saving 1 million people from death. Is any means justified to save them? Of course not. For example, killing 1 billion people would not be justified as a means to save 1 million people from death. For any end, we can consider means that are 10x as bad as the end, and the result is that the means is not justified. From one perspective, in the scenario of killing 1 to save 1 million, the absolutist deontologist justifies terrible means (i.e., letting 1 million people die) to the end of saving 1; of course, they would not word it this way, but it amounts to the same thing. Ultimately, for a particular end, no matter how bad, it is false that we can use any means possible to achieve that end and doing so would be morally permissible.

As Joseph Fletcher (a consequentialist) said, “‘Does a worthy end justify any means? Can an action, no matter what, be justified by saying it was done for a worthy aim?’ The answer is, of course, a loud and resounding NO!” Instead, “ends and means should be in balance.”[16]

A Sufficiently Positive End Can Justify a Negative Means

Let us investigate further just how negative of means can be justified. Let us reconsider Ice Cream with a more negative means. Clearly, Ice Cream does not justify shooting someone non-fatally in the leg to get the ice cream cone. For an end to even possibly justify non-fatal shooting, it would require something much more significant. Is there any scenario that would make a non-fatal shooting morally permissible? I think there is. Consider a scenario that is rigged such that if you non-fatally shoot a person, one billion people will be saved from a painful death. It should be obvious that preventing the death of a billion people does justify shooting someone non-fatally in the leg. Therefore, it is possible for a massively positive end to justify a negative means.

Uh oh! Did I just admit I am a horrible person? I think it is okay to shoot someone (non-fatally) if the circumstances justify it, after all. Of course, most people think it is permissible to kill in some cases, such as self-defense or limited instances of just war.[17] After explaining the typical EA stance on deferring to constraints including a document by MacAskill and Todd, and how MacAskill said that SBF violated them, Eric Levitz in the Intelligencer complains that “yet, that same document suggests that, in some extraordinary circumstances, profoundly good ends can justify odious means.” My response is, “Yes, and that is trivially correct.” If I could prevent 100,000,000 people from being tortured and killed by slapping someone in the face, I would and should do it. And that shouldn’t be controversial.

As MacAskill and Todd note (which the author also quotes), “Almost all ethicists agree that these rights and rules are not absolute. If you had to kill one person to save 100,000 others, most would agree that it would be the right thing to do.” If you will sacrifice a million people to save one person, you are the one that needs to have your moral faculties reexamined. Killing a person, while more evil than letting a person die, is not 999,999 times more evil than letting one person die. Probably, the value difference between killing a person and letting a person die is much less than the value of a person, i.e., the disvalue of letting a person die. Therefore, letting two people die is already worse than killing one person, but it even more obvious that letting 1,000,000 people die is worse than killing one person.

I do not believe I have said much that is particularly controversial when looking at these manufactured scenarios.[18] We are stipulating in these tradeoff considerations that the tradeoff is actually a known tradeoff and there is no other way, etc.

In sum, the ends don’t justify the means…except, of course, when they do. Ends don’t never justify the means and don’t always justify the means, and virtually no one in this debate thinks otherwise. Almost everyone thinks ends sometimes justify the means (depending on the means). What we have to do is assess the ends and assess the means to discern when exactly what means are justified for what ends.

Absolutism is the Problem

This whole question has very little to do with consequentialism or deontology, contrary to popular belief, and everything to do with absolute vs relative ethics (not individually or culturally relative, but situationally relative).[19] There is a debate internal to non-consequentialist traditions about this question of when the ends justify the means. For example, with deontology there is what is called threshold or moderate deontology, and in natural law theory there is a view called proportionalism. Neither of these are absolutist views, and both views include the results of actions as justification for some means. Internal to these non-consequentialist families of theories typically characterized as absolutist remains the exact same debate about ends-means reasoning. In fact, the most plausible theories in all moral families allow extreme (implausible but possible) cases to violate absolute rules.

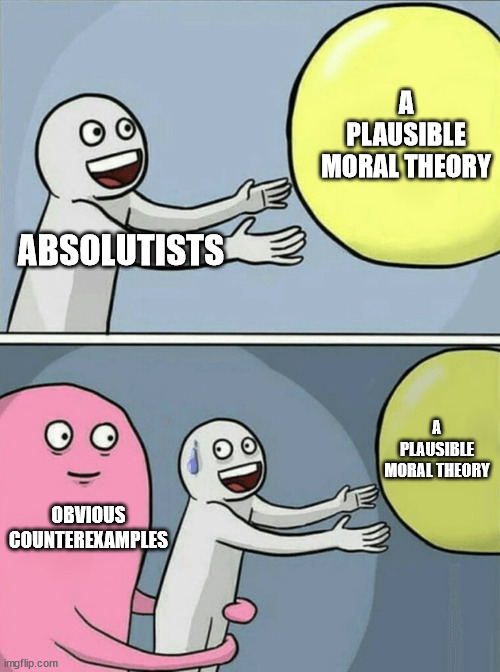

For example, it is uncommon to find a true absolutist deontologist among contemporary ethicists. As Aboodi, Borer, and Enoch point out, “hardly any (secular) contemporary deontologist is an absolutist. Contemporary deontologists are typically ‘moderate deontologists,’ deontologists who believe that deontological constraints come with thresholds, so that sometimes it is impermissible to violate a constraint in order to promote the good, but if enough good (or bad) is at stake, a constraint may justifiably be infringed.”[20] In other words, almost all (secular) deontologists also think the ends sometimes justify the means. Absolutism is subject to numerous paradoxes and counterexamples discussed previously and in the next subsection (see Figure 4)

Paradoxes of Absolute Deontology

Why is it that even deontologists think there are exceptions to constraints? Because absolute deontology is subject to substantial paradoxes and implausible implications that render it unpalatable, even worse than the alternatives. One example is the problem of risk, which is that any action raises the probability of violating absolute constraints, and no action gives 100% certainty of violating constraints. Therefore, it looks like the absolutist needs to say either that any action that produces a risk of violation is wrong, leading to moral paralysis since you would be prohibited from taking any action, or pick an (arbitrary) risk threshold, which implies that, in fact, two wrongs do make a right, and two rights make a wrong (in certain cases).[21] There have been responses, but what is perhaps the best response, stochastic dominance to motivate a risk threshold, is still subject to a sorites paradox that again appears to render absolutism false.[22] MacAskill offers a distinct but related argument from cluelessness that deontology implies moral paralysis.[23]

Alternatively, we can merely consider cases of extreme circumstances just like the one I gave earlier. A standard example is lying to a visitor to your house in order to prevent someone from being murdered, which Kant famously and psychopathically rejected. Michael Huemer considers a case where aliens will kill all 8 billion people on earth unless you kill one innocent person. Should you do so? The answer, as Huemer and any sane person agrees, is obviously yes.[24] (If the reader still thinks the answer is no, add another 3 zeros to the number of people you are letting die and ask yourself again. Repeat until you reject absolutism). These types of cases show quite quickly and simply that absolutism is not a plausible position in the slightest, and it is justified to do something morally bad if it results in something good enough (or, alternatively, prevents something way worse). There are other problems for absolutist deontology I neglect here.[25]

Of course, in a trivial sense, consequentialists are absolutist: it is always wrong to do something that does not result in the most good. However, that is not what anyone means when they call theories absolutist, which refers to theories that render specific classes of actions (e.g., intentional killing, lying, torture, etc.) as always impermissible.[26]

In summary, any plausible moral theory or framework has to reckon with the fact that something negative is permissible if it prevents something orders of magnitude worse. When people say “the end doesn’t justify the means” when condemning an action, they, in practice, more frequently mean those ends don’t justify those means. Equivalently, they mean that the ends don’t justify the means in this circumstance, rather than never, as the latter results in a completely implausible view.

Application to the FTX Scandal

So, where does that leave us in the FTX scandal? Everyone in the debate can say that, in this case, the ends did not justify the means. Although criticizing EA, Eric Levitz in the Intelligencer appears to challenge this, saying perhaps SBF may reasonably be considered justified if there are exceptions to absolute rules, “In ‘exceptional circumstances,’ the EAs allow, consequentialism may trump other considerations. And Sam Bankman-Fried might reasonably have considered his own circumstances exceptional,” describing the uniqueness of SBF’s case. Levitz asks, “If killing one person to save 100,000 is morally permissible, then couldn’t one say the same of scamming crypto investors for the sake of feeding the poor (and/or, preventing the robot apocalypse)?” If I were to put this into an argument, it may be: (1) if ends justify the means sometimes, then SBF’s actions are justified, (2) if EA, then ends justify the means sometimes, (3) if EA, then SBF’s actions are justified (or reasonably considered so).

There are several problems here (found in premise 1). First, it is not consequentialism that may trump other considerations, but consequences.[27] The significance of the difference is that any moral theory can say (and the most plausible ones do say) that consequences can, in the extreme, trump other considerations, as we saw earlier. Second, SBF’s circumstances may be exceptional in the generic sense of being rare and unique, but the question is “are they exceptional in the relevant sense,” which is that his circumstances are such that violating the constraint of committing illegal actions or fraud would result in a sufficient overall good to warrant breaking the constraint. It is a general rule that fraud is not good in the long run for your finances or moral evaluation.

Third, it is much too low a bar to say that it is reasonable for SBF to think that his circumstances were exceptional in the relevant sense, but we are (or should be) much more interested in whether SBF was correct in thinking his circumstances were exceptional in the relevant sense. An assessment of irrationality requires us to know his belief structure and evidence base for this primary claim as well as many background beliefs that informed his evidence and belief structure of the primary claim (and possibly knowing the correct view of decision theory, which is highly controversial).

Fourth, one can say anything one wants (see next section Can EA/Consequentialism/Longtermism be Used to Justify Anything?). We are and should be interested in what one can accurately say about such a comparison between killing one person to save 100,000 and ‘scamming crypto investors for the sake of feeding the poor (and/or, preventing the robot apocalypse).’ Fifth, it is unlikely that one can accurately say that these are comparably similar, such that it is incredibly unlikely that SBF was correct in his assessment. This rhetorical question about comparing saving 100,000 lives vs scamming crypto investors does very little to demonstrate otherwise.

SBF’s approach, which approved of continuing double-or-nothing bets for eternity, evidently did not consider the fallout associated with nearly inevitable bankruptcy and how that would set the movement back, as that would render each gamble less than net zero. Secondly, almost everyone agrees his approach was far too risk-loving. Nothing about EA or utilitarianism or decision theory, etc. suggests that we should take this risk-loving approach. As MacAskill and other EA leaders argue, we should be risk averse, especially with the types of scenarios SBF was dealing with (relevant EA forum post). Plus, there is the disvalue associated with breaking the law and chance of further lawsuits.

Levitz appears to accept the above points and concedes that it would be unfair to attribute SBF’s “bizarre financial philosophy” to effective altruism, and that EA leaders would likely have strongly disagreed with implementing this approach with his investments. Given Levitz’s acceptance of this, it is unclear what the critique is supposed to be from the above points. Levitz does move to another critique though, which is that EAs have fetishized expected value calculations, which I will address in the next section.

In summary, the ends sometimes justify the means, but violating constraints almost never actually produces the best result, as EA leaders are well-aware. Just because SBF made a horrible call does not mean that the EA framework is incorrect, as the typical EA framework makes very different predictions that would not include such risk-loving actions.

Effective Altruism is Not Inherently Utilitarian

There was a lot of confusion in these critiques about the connection between utilitarianism and effective altruism. Many of these articles assume that effective altruism implies or requires utilitarianism, such as (not including the quotes below) Erik Hoel, Elizabeth Weil in the Intelligencer, Rebecca Ackermann in MIT Technology Review (see a point-by-point response here), Giles Fraser in the Guardian, James W. Lenman in IAI News, and many more. I will survey and briefly respond to some individual quotations to this effect, showcase the differences between effective altruism and utilitarianism. Throughout, I will extensively refer to MacAskill’s 2019 characterization of effective altruism in “The Definition of Effective Altruism.”

As a first example, Linda Kinstler in the Economist (non-paywalled) writes “[MacAskill] taught an introductory lecture course on utilitarianism, the ethical theory that underwrites effective altruism.” Nitasha Tiku in The Washington Post (non-paywalled) writes, “[EA’s] underlying philosophy marries 18th-century utilitarianism with the more modern argument that people in rich nations should donate disposable income to help the global poor.” It is curious to call it 18th century utilitarianism when the version of utilitarianism EA is closest to (yet still quite distinct from) is “rule utilitarianism”, only hints of which were found in the 19th century with its primary development in the 20th century. Furthermore, while it may be a modern development that one can easily transfer money and goods across continents, it is certainly no modern argument that the wealthy should give disposable income to the poor, including across national lines. The Parable of the Good Samaritan advocates for helping explicitly across national lines, the Old Testament commanded concern for the poor by those with resources (for a fuller treatment, see Christians in an Age of Wealth: A Biblical Theology of Stewardship), and “the early Church Fathers took luxury to be a sign of idolatry and of neglect of the poor.”[28] The fourth century St. Ambrose condemns rich neglect of the poor, “You give coverings to walls and bring men to nakedness. The naked cries out before your house unheeded; your fellow-man is there, naked and crying, while you are perplexed by the choice of marble to clothe your floor.”[29]

Timothy Noah in The New Republic writes, “E.A. tries to distinguish itself from routine philanthropy by applying utilitarian reasoning with academic rigor and a youthful sense of urgency,” and also “Hard-core utilitarians tend not to concern themselves very much with the problem of economic inequality, so perhaps I shouldn’t be surprised to find little discussion of the topic within the E.A. sphere.” It is blatantly false that economic inequality is of little concern to utilitarians (as explained in the link that the author provided himself), including “hard-core” ones, as the state of economic inequality in the world leads to great suffering and death as a result. Now, it is correct that utilitarians do not see inequality as an intrinsic good, but merely an instrumental good. Yet, I do not see the problem with rejecting inequality’s intrinsic value rather than its instrumental value; it would be surprising that, on a perhaps extreme version of egalitarianism, there being two equally unhappy people is better than one slightly happy person and one extremely happy person. Alternatively, we should be much more concerned that people’s basic needs are met, so they are not dying of starvation and preventable disease, than we should that, if everyone already had their needs met, the rich have equal amounts of frivolous luxuries, as sufficientarianism well-accommodates. Finally, as MacAskill 2019 notes, EA is actually compatible with utilitarianism, prioritarianism, sufficientarianism, and egalitarianism (see next section).

Eric Levitz in the Intelligencer states, “Many people think of effective altruism as a ruthlessly utilitarian philosophy. Like utilitarians, EAs strive to do the greatest good for the greatest number. And they seek to subordinate common-sense moral intuitions to that aim.” EAs are not committed to doing the greatest good for the greatest number (see the next section for clarification), and they do not think any EA commitments subvert commonsense intuitions. In fact, EAs attempt to take common sense intuitions seriously along with their implications. The starting point for EA was originally that, if we can fairly easily save a drowning child, we should.[30] This is hardly a counterintuitive claim. Then, upon investigating the relevant similarities between this situation and charitable giving, we get effective altruism.

Jonathan Hannah in Philanthropy Daily asks, “why should we look to these utilitarians to learn how to be effective with our philanthropy?” First, we should look to EAs because EAs have evidence backing up claims of effectiveness. Secondly, again, EAs are not committed to utilitarianism, though many EAs are, in fact, utilitarians.

Theo Hobson in the Spectator claims, “Effective altruism is reheated utilitarianism… Even without the ‘longtermist’ aspect, this new utilitarianism is a thin and chilling philosophy.” Beyond the false utilitarianism claim, the accusation of thinness is surprising, since there are substantial and life-changing implications of taking EA seriously. These are profound implications that have resulted in protecting 70 million people from malaria, giving $100 million directly to those in extreme poverty, giving out hundreds of millions of deworming treatments, setting 100 million hens free from a caged existence, and much more. Collectively, GiveWell estimates the $1 billion donations through them will save 150,000 lives.

The aforementioned claims are misguided, as not everything that is an attempt to do the morally best thing is utilitarianism (see Figure 5).

Now, I seek to make good on my claim that effective altruism and utilitarianism are distinct. There are six things that distinguish EA from a reliance on utilitarianism, and I will examine each in turn:

- [Minimal] EA does not make normative claims

- EA is independently motivated

- EA does not have a global scope

- EA incorporates side constraints

- EA is not committed to the same “value theory”

- EA incorporates moral uncertainty

[Minimal] EA Does Not Make Normative Claims

Effective altruism is defined most precisely in MacAskill 2019, who clarifies explicitly that EA is non-normative. MacAskill says, “Effective altruism consists of two projects [an intellectual and a practical], rather than a set of normative claims.”[31] The idea is that EA is committed to trying to do the best with one’s resources, but not necessarily that it is morally obligatory to do so. Part of the reason for this definition is to be in alignment with the preferences and beliefs of those in the movement. There were surveys both to leaders and members of the movement in 2015 and 2017, respectively, which suggested a non-normative definition may be more representative to current EA adherents. Furthermore, it is more ecumenical, which is a desirable trait for a social movement as it expands.

Of course, a restriction to non-normative claims is limited, and Singer’s original argument that prompted many towards EA was explicitly normative in nature. His premises included talk of moral obligation. Many people in EA do think it is morally obligatory to be an EA. Thus, I think it is helpful to distinguish between different types or levels of EA, including minimal EA, normative EA, radical EA, and radical, normative EA.

Minimal EA makes no normative claims, while normative EA includes conditional obligations.[32] Normative EA claims that if one decides to donate, one is morally obligated to donate to the most effective charities, but it does not indicate how much one should donate. This could be claimed to be absolute, a general rule of thumb, or somewhere in between. Radical EA, on the other hand, includes unconditional obligations, but no conditional obligations. Brian Berkey, for example, argues that effective altruism is committed to unconditional obligations of beneficence.[33] Radical EA, as I characterize it, says one is morally obligated to donate a substantial portion of one’s surplus income to charities. Finally, radical, normative EA (RNEA) combines conditional and unconditional obligations of beneficence, claiming one is morally obligated to donate a substantial portion of one’s surplus income to effective charities. I expand on and defend these further elsewhere.[34]

Thus, while minimal EA does not include normative claims, there are expanded versions of EA that include conditional and/or unconditional obligations of beneficence. Minimal EA, then, constitutes the core of the EA theory, while these claims of obligations constitute auxiliary hypotheses of the EA theory. Since the core of EA does not include normative claims, it cannot be identical to (any version of) utilitarianism, whose core includes a normative claim to maximize impartial welfare.

EA is Independently Motivated

Effective altruism is distinct from utilitarianism in that EA can be motivated on non-consequentialist grounds. In fact, even Peter Singer’s original argument, inspiring much of EA, was non-consequentialist in nature. Singer’s original “drowning child” thought experiment relied only on a simple, specific thought experiment, proposing midlevel principles (principles that stand in between specific cases and moral theories) to explain the intuition from the thought experiment, and deriving a further conclusion by comparing relevant similarities in the thought experiment to a real world situation, all of which is a standard procedure in applied ethics. Of course, this article has been critically responded to in the philosophy community many, many times, some more revolting[35] than others,[36] but many (such as I) still find it a compelling and sound argument that also demonstrates EA’s independence from utilitarianism.

Theory-Independent Motivation: The Drowning Child

Singer’s original thought experiment is: “if I am walking past a shallow pond and see a child drowning in it, I ought to wade in and pull the child out. This will mean getting my clothes muddy, but this is insignificant, while the death of the child would presumably be a very bad thing.”[37]

Singer proposes two variants[38] of a midlevel principle that would explain this obvious result:

- If it is in our power to prevent something bad from happening, without thereby sacrificing anything of comparable moral importance, we ought, morally, to do it.

He also proposed a weaker principle,

- If it is in our power to prevent something very bad from happening, without thereby sacrificing anything morally significant, we ought, morally, to do it.

These principles are extremely plausible, are quite intuitive, and would explain why we have the intuitions we do in various rescue cases comparable to the above. Next, Singer defended why this principle can be extended to the case of charitable giving by examining the relevant similarities. The reasoning is that, given the existence of charities, we are in a position to prevent something bad from happening, e.g., starvation and preventable disease. We can do something about it by ‘sacrificing’ our daily Starbucks, monthly Netflix subscription, yearly luxury vacations, or even more clearly unnecessary purchases, for example additional sports cars or boats that are not vocationally necessary, etc. None of these things are (obviously) morally significant, and they are certainly not of comparable moral importance of the lives of other human beings. Therefore, we have a moral obligation to take action in donating to effective charities, particularly from the income that we are using for surplus items.

Notice that we did not appeal to any kind of utilitarian reasoning in the above argument, and one can accept either of Singer’s midlevel principles without accepting utilitarianism. This example shows how effective altruism can be independently motivated apart from utilitarianism. This fact was pointed out previously by Jeff McMahan when he noticed that even philosophical critiques of EA make this false assumption of reliance on utilitarianism. McMahan, writing in 2016, said, “It is therefore insufficient to refute the claims of effective altruism simply to haul out [Bernard] Williams’s much debated objections to utilitarianism. To justify their disdain, critics must demonstrate that the positive arguments presented by Singer, Unger, and others, which are independent of any theoretical commitments, are mistaken.”[39]

Martin Luther’s Drowning Person

Interestingly, the Christian has a surprising connection to Singer’s Drowning Child thought experiment, as a nearly identical thought experiment and comparison was made by Martin Luther in the 16th century.[40] In his commentary on the 5th commandment “Thou shalt not kill” in The Large Catechism, Luther connects the commandment to Jesus’ words in Matthew 25, “For I was hungry and you gave me nothing to eat, I was thirsty and you gave me nothing to drink, I was a stranger and you did not invite me in, I needed clothes and you did not clothe me, I was sick and in prison and you did not look after me.” Luther then gives a drowning person comparison: “It is just as if I saw some one navigating and laboring in deep water [and struggling against adverse winds] or one fallen into fire, and could extend to him the hand to pull him out and save him, and yet refused to do it. What else would I appear, even in the eyes of the world, than as a murderer and a criminal?”

Luther condemns in the strongest words those could “defend and save [his neighbor], so that no bodily harm or hurt happen to him and yet does not do it.” He says, “If…you see one suffer hunger and do not give him food, you have caused him to starve. So also, if you see any one innocently sentenced to death or in like distress, and do not save him, although you know ways and means to do so, you have killed him.” Finally, he says, “Therefore God also rightly calls all those murderers who do not afford counsel and help in distress and danger of body and life, and will pass a most terrible sentence upon them in the last day.”

Virtue Theoretic Motivation: Generosity and Others-Centeredness

Beyond a theory-independent approach to motivate EA, we can also employ a non-consequentialist theory, virtue ethics, to motivate EA. Some limited connections between effective altruism and virtue ethics have been previously explored,[41] but I will briefly give two arguments for effective altruism from virtue ethics. Specifically, I will argue from the virtues of generosity and others-centeredness for normative EA and radical EA, respectively. Thus, if both arguments go through, the result is radical, normative EA.

First, I assume the qualified-agent account of the criterion of right action[42] of virtue ethics given by Rosalind Hursthouse.[43] Second, I employ T. Ryan Byerly’s accounts of both generosity and others-centeredness.[44] Both of these, especially from the Christian perspective, are virtues. The argument from generosity is:

- An action is right only if it is what a virtuous agent would characteristically do

- A virtuous agent would characteristically be generous

- To be generous is to be skillful in gift-giving (i.e., giving the right gifts in right amounts to the right people)

- A charitable donation is right only if it is skillful in gift-giving

- A charitable donation is skillful in gift-giving only if it results in maximal good

- A charitable donation is right only if it results in maximal good (NEA)

The argument from others-centeredness is:

- An action is right only if it is what a virtuous agent would characteristically do

- A virtuous agent would characteristically be others-centered

- To be others-centered includes treating others’ interests as more important than your own

- Satisfying one’s interests in luxuries before trying to satisfy others’ interests in basic needs is not others-centered

- An action is right only if it prioritizes others’ basic needs before your luxuries

- A substantial portion of one’s surplus income typically goes to luxuries

- Therefore, a person is morally obligated to donate a substantial portion of one’s surplus income to charity (REA)

I don’t have time to go into an in-depth defense of these arguments (though see my draft paper [pdf] for a characterization and assessment of luxuries as in the above argument, as well as independent arguments for premises 5-7 regarding others-centeredness), but it at least shows how one can reasonably motivate effective altruism from virtue ethical principles.

EA Does Not Have a Global Scope